There is nothing that I shudder at more than the idea of a separation of the Union. Should such an event ever happen, which I fervently pray god to avert, from that date, I view our liberty gone–It is the durability of the confederation upon which the general government is built, that must prolong our liberty, the moment it separates, it is gone.

-Andrew Jackson

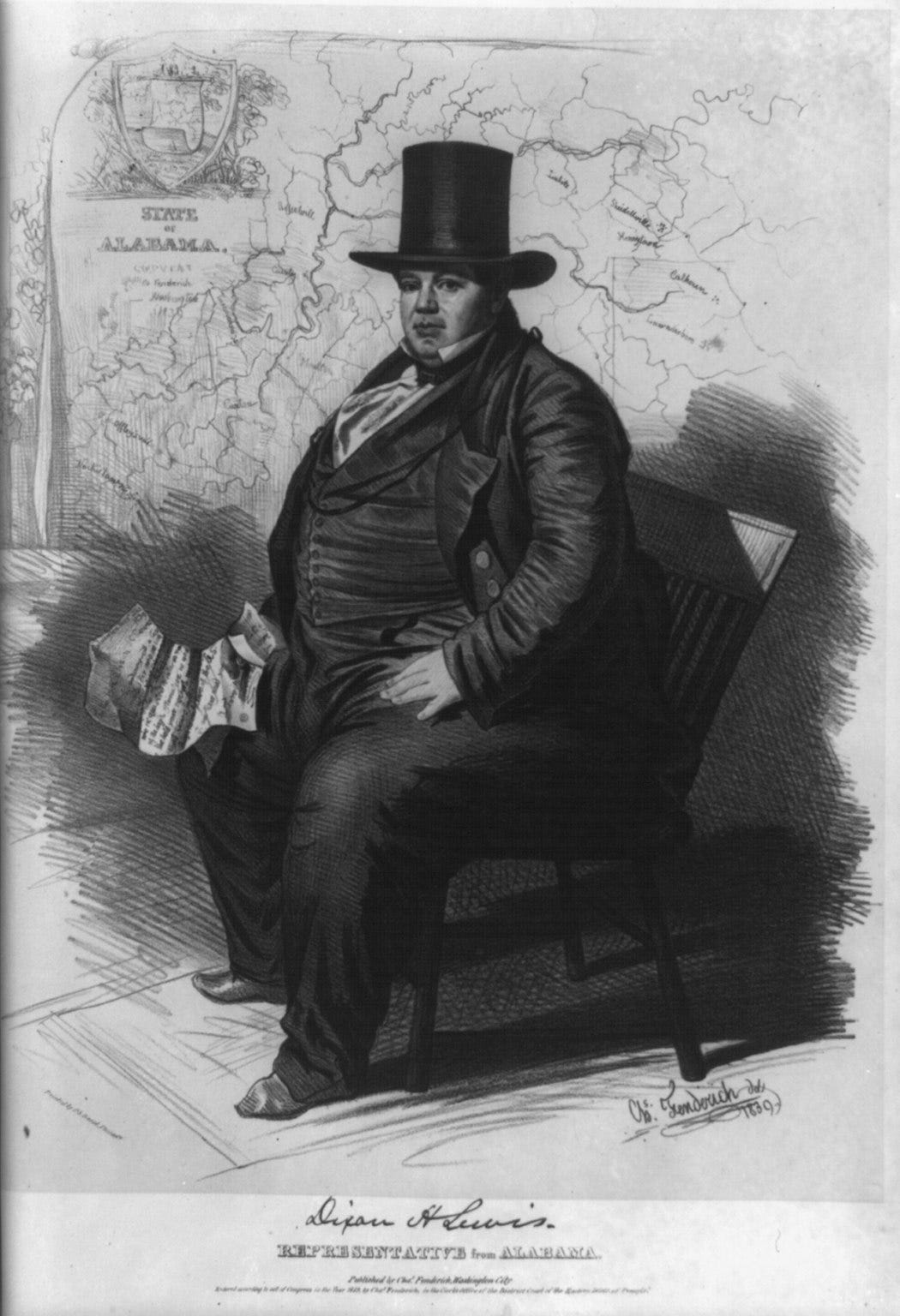

Discovering Dixon Hall Lewis

While I was reading American Lion by Jon Meacham, I came across a description of a Congressman during the Andrew Jackson era, Dixon Hall Lewis, which prompted my curiosity to look for a picture of him. The description states, “Dixon Hall Lewis–a nearly five hundred pound giant of a man who chaired the House Indian Affairs Committee.” After I found his picture, I became more interested in his story. Today I will share a few details of his story that demonstrate the political happenings of the tumultuous antebellum era in the United States and of the presidency of Andrew Jackson.

Dixon Hall Lewis was born in 1802 in either Dinwiddie County, Virginia, or Hancock County, Georgia. He graduated from South Carolina University. After graduating he moved to Alabama where he was elected in 1826 and served two additional terms in the lower house of the Alabama legislature and went on in 1828 to be elected to the U.S. House of Representatives and later in 1834 to the U.S. Senate. He was noted to be a talented orator. Lewis was married to a woman named Susan Elizabeth Elmore with whom he had seven children.

Lewis in his time in Alabama’s state legislature had been involved in creation of legislation that extended the states’ authority over all Native American land within its boundaries. This land had previously been promised to the Native Americans in treaties made with the federal government.

States’ Rights in the Jackson Era

One issue that Jackson and Lewis differed on was the right of a state to declare null and void a tariff policy which the Southern planter states did not agree with. The first protective tariff of 1816, in reaction to the war with Britain, had received support from most states, but the 1828 Tariff of Abominations did not have as widespread support. Southern states felt it too strongly favored Northern industry over the Southern planter states. Southern states began to favor nullification of the tariffs, declaring them null and void within their state boundary. Though Jackson could understand the concern with the perceived inconsistent benefit of the tariff he strongly opposed the notion of nullification, viewing it as a threat to national unity. Jackson even threatened force to enforce the tariffs and protect national unity in 1832 through a proclamation.

The crisis of nullification was ultimately averted through a compromised tariff negotiated by Henry Clay. Lewis would prove to be an important figure in the state of Alabama that pushed the state ideology more toward the importance of states’ right versus what Jackson saw as most important, national unity.

Public perception of obesity in the 1800’s

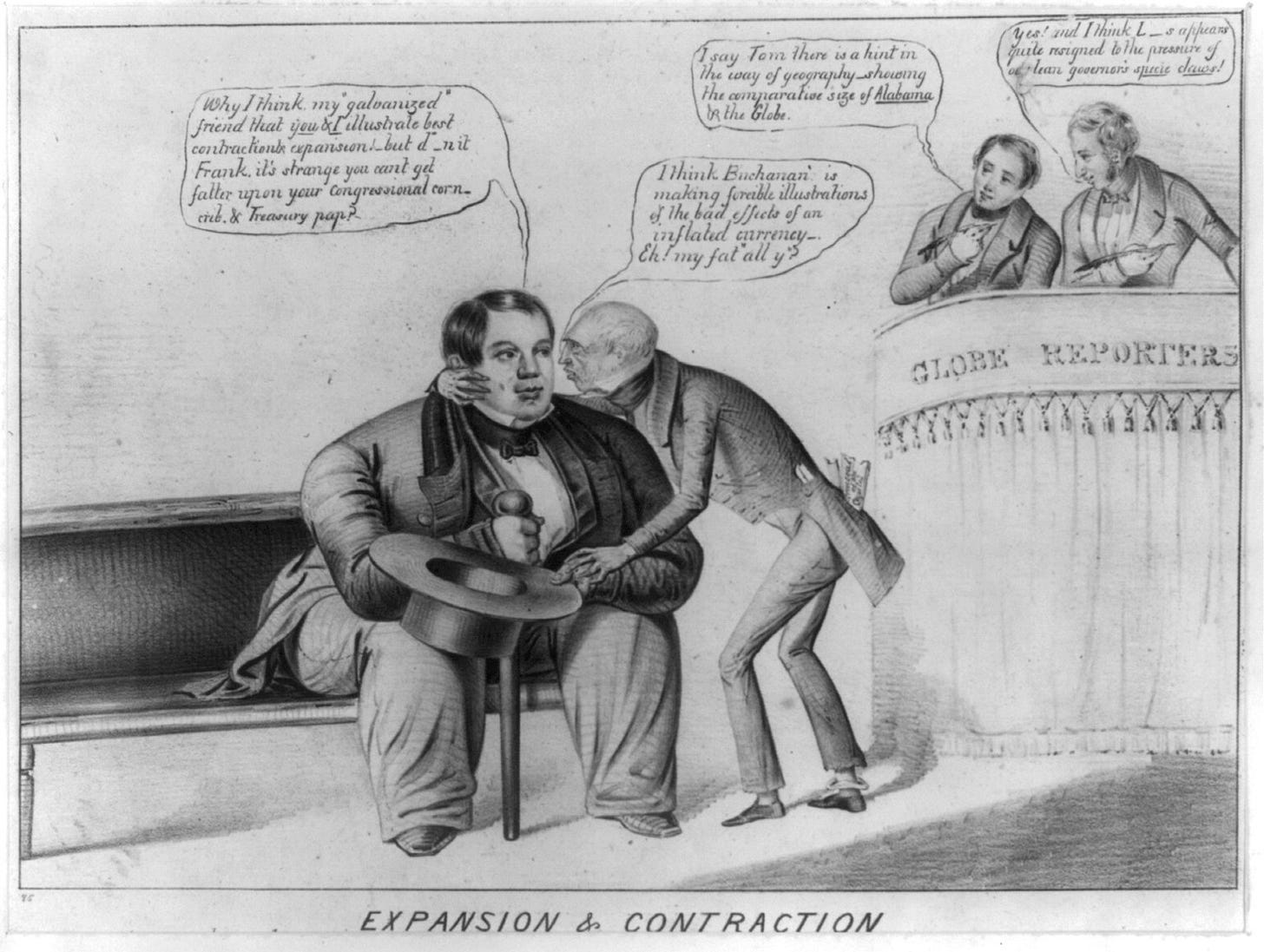

Considering the commentary I have seen on larger politicians of our day who weigh far less Lewis, I can imagine if a Congress person weighed over 400 pounds today they would be a target for criticism and ridicule. This made me wonder what was the perception of Lewis given his obesity, which in his time probably would have been less common. I was able to find commentary that was ridiculing but also some that fortunately was more supportive:

“Among other rumors is one that the Hon. Dixon H. Lewis has agreed to walk for the next Presidency. As for so large a gentleman running for that office it would be out of the question. He never ran in his life but once, and that was when his sweetheart told him if he could not catch her he could not have her.’” The Sunbury Gazette, Sunbury Pennsylvania, February 14, 1846

“The New Bedford Bulletin relates the following story of the Hon. Dixon H. Lewis, Member of Congress from Alabama. It is said of Dixon H. Lewis (who is so large that he occupies three seats in a stage coach, but is elected to but one in Congress), that while looking round for a sufficiently capacious chair, at a public meeting, an old fashioned man cried out, ‘Three cheers for Lewis!’ whereupon three chairs were brought in and the great man comfortably seated amid the applause of the audience.” The Weekly Telegraph, Macon Georgia, October 11, 1842

“When Mr. Dixon H. Lewis obtained the floor this morning, there was some speculations as to whether he could manage to occupy his house. His friends calculated that his physical strength would not permit him to speak longer than thirty minutes. They were mistaken, for at the expiration of the hour, he appeared to have but just entered on his subject. Not withstanding his weight, he is extremely active, and can if he chooses skip up the Capitol steps with the agility of Cinderella in her glass slippers.” The Baltimore Sun, July 12, 1842

“Dixon H. Lewis, whether we regard the physical, the mental, or the moral man, was cast in no ordinary mold. The more than usual proportions which distinguished him physically, but typified the large and comprehensive grasp of the intellect which was his, and which directed the impulses of a heart which beat in unison with all that was generated or elevated in man.” Spirit of the South, Eufaula, Alabama, December 26, 1848, soon after his death

Was Lewis a cemetery enthusiast?

At the age of forty-six, Dixon Hall Lewis ended up in New York in the last days of his life. He had gone there due to medical issues, and he was noted to have friends in the area. Interestingly, a man who during his career was a spokesman for Southern states’ rights ended up being buried in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York.

Lewis was noted to have visited the cemetery about a year before his death and was enchanted with it. He stated to those around him his appreciation of the beauty of the cemetery and his wish that this be his final resting place.

Though Lewis had spent his career fighting for Alabama’s right to secession from the union, after his death, he was heralded by a New York paper as a man of the Union:

“And if I might express the feeling of the community by whom his remains were given back to the dust from which they came, it would be responsive to his own—that they may rest where, in the order of Providence, the thread of his life was severed—among those whose mournful privilege it was to enshrine them with the ashes of their own kindred. If this feeling shall be gratified, his family, his friends, the state he represented here, may be assured that he will lie among us, not as a stranger, but as one of ourselves—children alike of a common Union, and heirs of a common prosperity and fame.” New York Daily Herald, August 16, 1846

Perhaps the New York Daily Herald, through honoring his legacy as an esteemed United States Congressman was making the case for a stronger American union in a divided time of the young nation, a sentiment that Old Hickory would have appreciated.

Sources:

https://encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/dixon-hall-lewis/

Meacham, J. (2008). American Lion: Andrew Jackson in the White House. 1st large print ed. Random House Large Print.

I enjoyed researching Lewis, he is an interesting character. The theme here is contradictions during this time and I will have two more characters whose story show contradictions in the times of what you might assume to be the case versus the reality of the situation. The way that Lewis was remembered I thought was a very interesting contradiction to what he actually stood for.

I thought it was super interesting that there was a reference to Cinderella in one of the newspaper clips about Lewis and that the description was so visual: "Not withstanding his weight, he is extremely active, and can if he chooses skip up the Capitol steps with the agility of Cinderella in her glass slippers."

I, of course, think of the animated Disney cartoon but that wouldn't be the frame of reference for 1842.