In reading about the life and work of Frances “Fannie” Wright, who lived from 1795-1852, a proverb comes to mind: “the path to hell is paved with good intentions.” One interpretation of this proverb could be a person having good intentions but not acting on them. This was not the case for Wright. Wright did act on her good intentions, but factors at the time prevented these actions from creating the results she had hoped for.

The early years

Wright was born on September 6, 1795, in Dundee, Scotland, to her parents Camilla Campbell and James Wright. Her father was a wealthy man who was a manufacturer of linen. He had correspondence with well-known American and French thinkers of his day including the Marquis de Lafayette. Unfortunately, both of her parents as well as her older brother died when Wright was young, and her and her younger sister, Camilla, were orphaned.

Initially, they were sent to a maternal aunt who had interest in the French philosophers of the Age of Enlightenment and passed that interest onto Wright. At the age of sixteen, Wright and her sister moved in with a great uncle, James Mylne, who was a philosophy professor at Glasgow University. Here Wright picked up further interest in the work of Greek philosophers. By the time she was eighteen years old, she’d written a book titled A Few Days in Athens about the philosopher Epicurus. She also became interested in history as well as the early evolution of the democratic government of the United States.

It must have been fascinating for Wright to observe the infancy of this government formed on the basis of many of the ideas of the philosophers whose works she had studied. More excitement was to come for her, as she would have the opportunity to travel to America and meet some of the masterminds behind this experiment.

Travel to the United States

At the age of twenty-three, Wright made a trip to America with her sister. From this experience, she published a book titled Views of Society and Manners in America. The work opened Wright to a circle of powerful acquaintances. She began to travel in France with the Marquis de Lafayette in 1821, and then, in 1824, she and her sister joined him in his farewell tour around America where she met many important figures of the time including Thomas Jefferson.

If you recall from my previous Silent Sod post, Thomas Jefferson stated in a letter to Wright regarding her experiment to abolish slavery, “Every plan should be adopted, every experiment tried, which may do something towards the ultimate object. that which you propose is well worthy of trial. It has succeeded with certain portions of our white brethren, under the care of a Rapp and an Owen; and why may it not succeed with the man of color?”

Who were Rapp and Owen that Jefferson referred to?

New Harmony

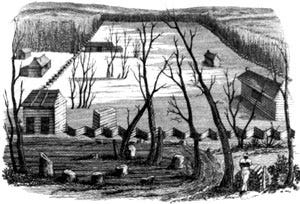

Wright came to know of a social experiment in New Harmony, Indiana, and even participated in it. The town was originally founded in 1814 by a man named George Rapp. The original settlement was a group of people who were Lutherans and had separated from the official church in Germany and settled in the United States. They held a belief in staying in this settlement until the end of world and at some point practiced celibacy. Eventually, they left the settlement and a Welsh industrialist named Robert Owen bought it in 1825, and attempted to create a utopian society dedicated to equality through education, science, technology and communal living.

Wright visited New Harmony at different times when it was lead by both Rapp and Owen. She was inspired by the notion of promoting equality through education and decided to establish her own community modeled after these beliefs. Rapp’s and Owen’s New Harmony communities were both for white people, but Wright envisioned a community that would allow enslaved Blacks to work toward their freedom while receiving training and education.

Wright’s plans involved purchasing enslaved people, having them work in the community to pay for their freedom, and then having them sent to Haiti or Liberia. She believed that her settlement could be a model for others to see that they could provide freedom to enslaved people without amassing debt.

Wright’s experiment: Nashoba Community

In 1826, Wright bought an approximately 320 acre piece of land along the Wolf River in Tennessee about thirteen miles from Memphis. She purchased enslaved Black people from nearby plantations. They came to live at the settlement alongside whites who were willing to join the community and work.

Although Wright did get input from various top minds of the time such as Lafayette and Jefferson, the land that was selected for Nashoba was mosquito infested. Not only did this not allow for crops to thrive but also resulted in Wright contracting malaria, for which she had to leave the community.

By time she was able to return in 1828, the community had sunk into despair due to poor management, leaders who were too harsh in their punishment to the enslaved community, and scandals that erupted over an interracial relationship that developed between a white supervisor and a recently freed Black woman.

The community failed and would not serve as a model for others in America to establish land to allow enslaved Blacks to work for freedom. An article in the Onondaga Standard in May 19, 1830 read:

“It was recollected that Miss Frances Wright lately went to Haiti to plant thirty colored people taken from this country at her own expense. For this philanthropic act she certainly deserves respect and praise, whatever may be her errors of opinion, or eccentricities of life. Her arrival at the island prompted the Haitian muse to salute her.”

Wright’s legacy and a visit to her grave

I was able to pay a visit to Frances Wright’s grave at Spring Grove Cemetery, in Cincinnati, Ohio. Wright at some point married and had a daughter, and eventually settled in Cincinnati. She later was divorced and became estranged from her daughter.

I found an obituary about her that I thought was an interesting commentary on how she was viewed by some sections of society at the time in the Courier-Journal of Louisville, Kentucky, dated December 16, 1852:

“Death of Fanny Wright–Madam D’Arusmont, better known as Fanny Wright, died at her residence in Cincinnati last Monday evening. Her death is said to have been the consequence of a fall which she received some months ago. She was a woman of powerful intellect, great acquirements, singular boldness of thoughts, and extraordinary eloquence, and we believe that she entertained a sincere and earnest desire to promote the true interests of the world, but she had wrong views of religion and of the most important institutions of civilised society, and all her labors tended to mischief and not to good.”

Wright was a strong advocate for the separation of church and state and was outspoken against organized religion, believing that kind feelings and actions should be the only religion. True to her life, the words on her grave read:

“I have wedded the cause of human improvement, staked on it my fortune, my reputation and my life.”

Conclusions

Francis Wright may not have been able to get the results she hoped for in her social experiment, and it seems that her friend Robert Owen has similar results in his own trial in New Harmony, Indiana, which also at some point due to internal quarreling went into disarray after about two years. Many leaders in America during her time acknowledged the evils of slavery yet they concluded that it would be impossible to abolish it at the time. Wright at least made an effort at progress, but upon reflection I think it is important to ask: why was the solution for Blacks who had invested in the country to leave it? Was Wright unable to envision a country where both races could live freely even as progressive as she was for her time? I enjoyed learning about her life and one day I would love to visit New Harmony, Indiana, which still has many historical sites left from this fascinating era.

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frances_Wright

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_Harmony,_Indiana

https://heritage.humanists.uk/frances-wright/

I love the contrast between the description of Frances Wright that appeared in her obituary in the newspaper versus the epitaph she has on her gravestone.

Newspaper - "all her labors tended to mischief and not to good"

Epitaph - "I have wedded the cause of human improvement, staked on it my fortune, my reputation and my life.”

What a fascinating woman! The difference between her obit and her epitaph is quite telling. I'd be curious to read her books as well as visit New Haven, too. (As I was reading and she caught malaria, I expected *that* to do her in.)