Every day right after I do my Wordle, I play the New York Times game Connections. If I successfully solve it, I’ll then celebrate by singing “It’s Connections!” to the tune of “It’s electric!” in the “Electric Slide.”

I just wrapped up a ten day trip to Washington DC, New York City, and Boston with my uncle. We flew into DC, took the train up the coast, and then flew out of Boston, spending about three days in each city.

I expected to encounter a lot of inspiration for new posts on The Silent Sod, but what I didn’t anticipate was how much I would encounter that ties into what I’ve already written about on here.

It’s Connections!

Finding Charles Finnemore and the 54th Mass

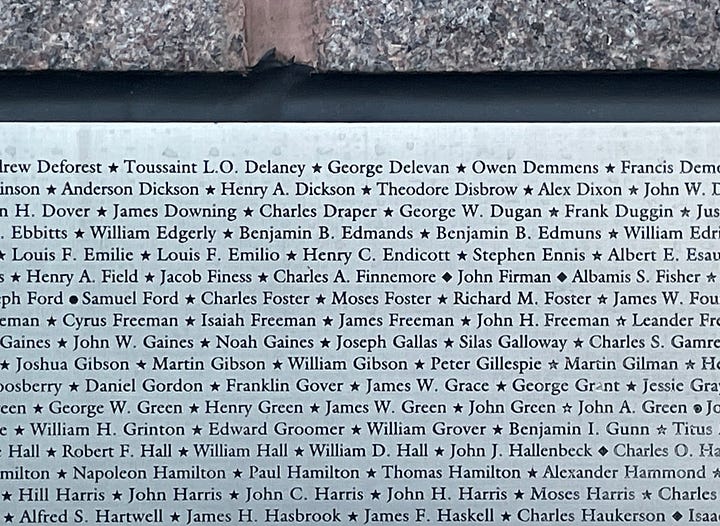

Back in February, I wrote about the Black Civil War soldiers in the 54th Massachusetts regiment and their role in the Battle of Olustee. In February 2023, I’d traveled to a reenactment of this battle in Florida while I was living in Atlanta, and then in February 2024 while living in Amherst, I’d learned about Charles Finnemore, a local resident who was a member of the 54th Massachusetts and who was wounded at Olustee.

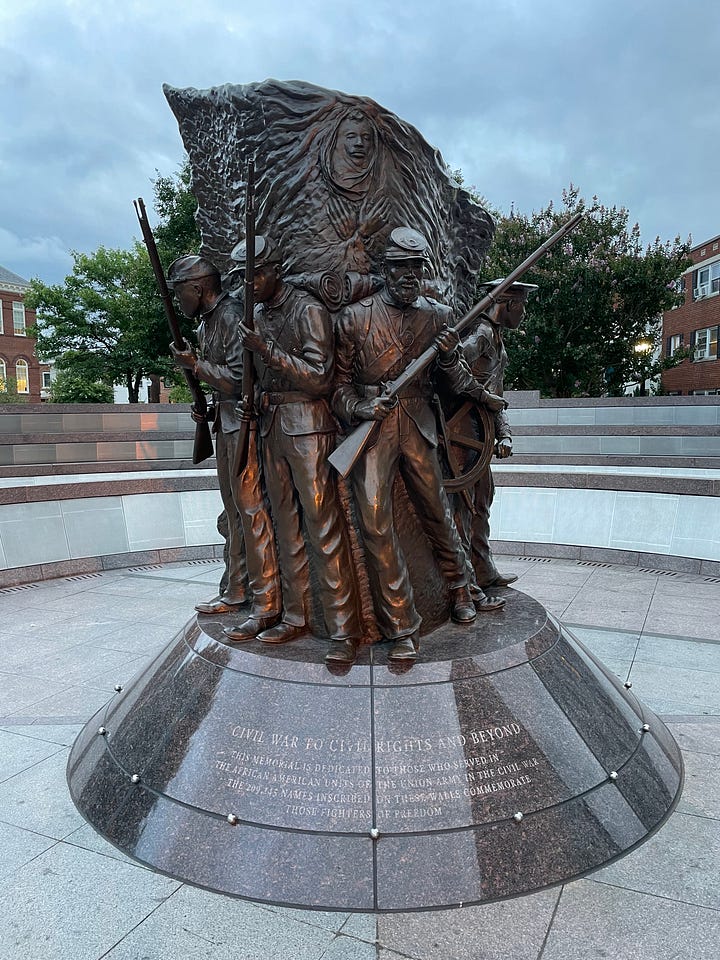

In Washington DC, we stayed in the Shaw neighborhood near the African American Civil War Memorial, which includes the names of 209,145 soldiers who were part of the United States Colored Troops. It took a few visits to find him, but I eventually located Charles Finnemore:

Speaking of the 54th Massachusetts, at the National Gallery in DC, I saw a plaster version a monument made to honor this regiment and their white commander, Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, who died during the Second Battle of Fort Wagner. A few days later, I saw the bronze monument on the Boston Common, and thanks to reading a post that morning on Civil War Memory, one of my favorite Substacks, I knew I was seeing the monument on the 161st anniversary of the battle. This battle was especially significant because the 54th Massachusetts Regiment led the charge, suffered heavy casualties, and through their efforts, demonstrated that Black soldiers could make significant contributions to the Union Army.

A cyclorama redux

If you’re someone who’s into museums, a trip to Washington DC is a must do. There are a ton of museums on the mall, many of them part of the Smithsonian Institution, and all of them offering free entry as far as I could tell.

My uncle and I had planned to visit the National Gallery and the Museum of American History, but because we had extra time, we also made it to the Museum of Natural History and the Hirshhorn Museum. I’d never heard of the Hirshhorn, a contemporary art museum, before my visit, but I feel like fate had a hand in guiding me there because seeing Mark Bradford’s Pickett’s Charge was one of the highlights of my trip.

The piece takes its inspiration from Civil War cycloramas like The Battle of Atlanta cyclorama, whose changing interpretation over time I wrote about here. Bradford based his work on an 1883 cyclorama depicting Pickett’s Charge by Paul Philippoteaux that you can find today at Gettysburg National Military Park.

Bradford used images from the original cyclorama to create eight large abstract paintings that are displayed in a circular gallery at the Hirshhorn. Per the museum’s site, Bradford’s “work weaves together past and present, illusion and abstraction, inviting visitors to reconsider how narratives about American history are shaped and contested.”

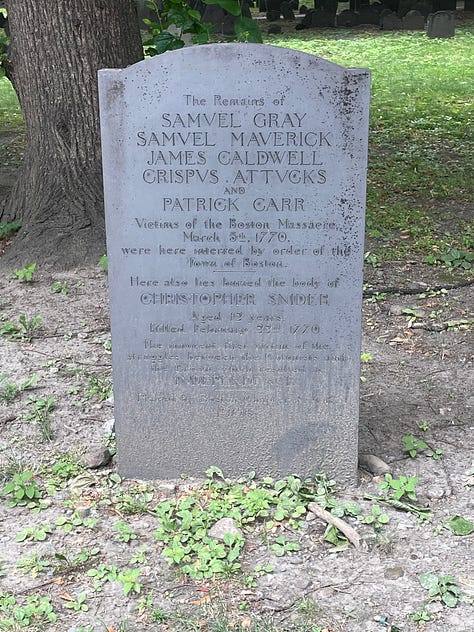

The Boston Massacre

A week or so before I left for my trip, I wrote about Massacre Day, a day observed in Boston between 1771-1883 to honor the victims of the Boston Massacre. My post focused particularly on the legacy of Crispus Attucks, an African and Indigenous man killed by British soldiers. Attucks was first whitewashed out of the incident by Paul Revere, who made an engraving of the scene, then blamed for the attack by John Adams in his defense of the British soldiers, and finally, nearly one hundred years later around the time of the Civil War, held up as an example of Black patriotism.

In Boston, I was able to visit the spot where the massacre took place right outside of the Old State House, and at the Granary Burying Ground, I saw the gravestone for the victims of the massacre as well as Paul Revere’s.

Changing narratives

Just as Crispus Attuck’s legacy was revived around the time of the Civil War as a model of patriotism, so too was Paul Revere’s. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem “Paul Revere’s Ride,” published in January 1861, although in many ways factually inaccurate, cemented Revere’s heroic image. I learned in Boston there were other riders besides Revere, including women, and Revere would have never shouted “the British are coming” because he didn’t want to be caught by soldiers already stationed there.

According to the information on the placard near “The Shaw 54th Regiment Memorial” at the National Gallery, the monument was initially intended to be a standalone equestrian statue of Shaw like that shown for Revere above, but Shaw’s family insisted the men of his regiment be depicted alongside him. The bronze monument was unveiled in Boston in 1897 during an era when many Confederate monuments were being erected across the country. The portrayal of Black soldiers fighting for emancipation stood in contrast to memorializations of the Confederacy which downplayed or ignored the role of slavery in the conflict. The African American Civil War Memorial in Washington DC was dedicated in 1998 over 130 years after the war.

I share this information about the timeline for these different monuments and the changing narratives of Crispus Attucks and Paul Revere because it underscores one of the major themes of The Silent Sod that I encountered over and over again on my trip: the memory of the dead is in the hands of the living.

Who is elevated, who is celebrated, who is (R)evered, changes over time, and what we’re seeing in our modern era in the United States is not necessarily an attempt to erase history but rather a reckoning with how white male patriarchs have been deified in our culture of memorialization.

There’s a history to our history, and I hope we can keep shedding light on this here on The Silent Sod.

Another terrific post -- one with a lot of hometown resonance for me (Crispus Attucks and I both grew up in Framingham, MA, though at very different points in history!)

Do you know Robert Lowell's poem "For The Union Dead"? It was inspired by the monument to Shaw and the 54th Massachusetts, written by the scion of one of the Brahmanest of Boston Brahman families: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/57035/for-the-union-dead