Living in the Northeastern United States for the first time is exposing certain gaps in my knowledge of Revolutionary War history.

Recently, I attended a tour of the Old Hadley Cemetery, a nearby Massachusetts town burial ground established in 1660. The tour focused on connections between the revolution and funerary imagery, and I was surprised to learn that Greek and Roman symbols on gravestones (e.g., urns) can be tied to the fact that the US was founded on the democratic principles of these classical cultures. I’ve always assumed people just thought Greek and Roman funerary imagery was cool, not that they were trying to make a statement about being free from the British monarchy.

Everyone knows about the Boston Massacre?

As part of the tour, the guide gave us a rundown of events that preceded the Revolutionary War (e.g., the Townsend Acts, the death of 11 year old Christopher Seider, and the Boston Tea Party). When the guide arrived at the part of the timeline where the Boston Massacre occurred, which happened shortly after Seider’s death and over three years before the Boston Tea Party, she said to the crowd by way of summary: “everyone knows about the Boston Massacre.”

Although I’d heard of it before, I couldn’t remember exactly what happened. I wanted to raise my hand, apologize for being from Ohio, and ask for an explanation, but I didn’t. Instead, I spent about a month continuing in my state of ignorance before finally listening to a lecture about it from the Great Courses series Ordinary Americans in the Revolution.

Enter Crispus Attucks

Crispus Attucks is one of those names like Benedict Arnold, Nathan Hale, or John Hancock that I associate with the American Revolution but don’t necessarily understand what role they played in the conflict. (I do know Benedict Arnold was a traitor!)

Turns out, Crispus Attucks is a central figure in the Boston Massacre, which took place March 5, 1770, about five years before the start of the Revolutionary War. At the time of the massacre, British soldiers had been occupying Boston for about a year and a half in order to suppress violent outbursts among the colonists who were upset about taxation policies.

Attucks was one of five men killed when British soldiers accidentally(?) opened fire on a group of colonists. The situation started as an argument between a thirteen year old Boston apprentice and a British soldier and escalated into a standoff between a small group of British soldiers and a crowd of angry colonists.

Here’s a depiction of the event by Paul Revere, who it turns out was an engraver and a Patriot looking to stir up some stuff, before he took his famous ride:

There are a couple of things wrong with this picture. One is that Revere depicts all the British soldiers firing into the crowd at the same time on the order of their commander when apparently the first shot was accidental, the others followed in quick succession, and none of them were done under orders. The second thing that’s wrong with Revere’s picture is that it doesn’t include Crispus Attucks, who was of mixed African and Indigenous ancestry. Revere’s crowd of colonists are all depicted as white.

While Revere whitewashed the scene, another Founding Father, John Adams, defended the British soldiers involved in the attack in court by blaming the incident on Crispus Attucks and others in the crowd, who he described as "a motley rabble of saucy boys, Negroes, and mulattos, Irish teagues and outlandish jack tars." Of the nine soldiers tried, only two were convicted, and their sentences were significantly commuted.

About ninety years later around the time of the Civil War, Crispus Attucks’s legacy was revived when his story was highlighted by abolitionists and included as an example of patriotism in William Cooper Nell’s The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution.

Massacre Day

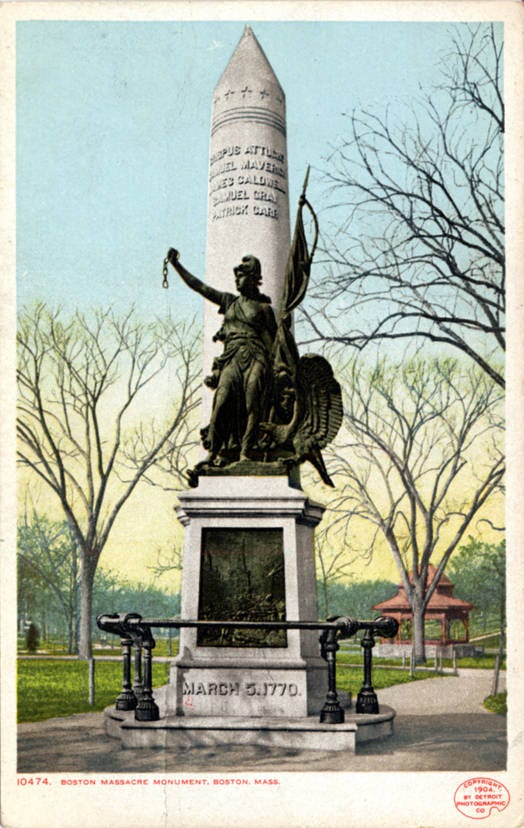

One other takeaway from my Old Hadley Cemetery tour was that after the 1770 incident, Bostonians observed Massacre Day annually on March 5th until the end of the Revolutionary War in 1883. After they’d gained their independence, the Bostonians shifted their attention to celebrating July 4th. However, March 5th is now observed as Crispus Attucks Day in Boston, and he and the other four victims are remembered in this monument on the Boston Common:

Boston recommendations?

I’m hoping to check out this monument in person when I visit Boston soon. Please let me know if you have any other recommendations of historical sites I should visit while I’m there.

Wow, I learned something new! I wonder if that book you mentioned is still in print. Very interesting!

Thank you, Sarah, this is fantastic. I've made a point of plugging the many gaping holes in my knowledge of the Revolutionary War period. I too, had heard of Crispus Attucks, but only a vague notion (perhaps a shadow memory from a trip to Boston decades ago.)

What a fascinating lesson. Thank you. Your story sent me chasing down this "The colored patriots of the American Revolution," published in 1855. It turns out the book is available on the Internet Archive with full text search. (Swoon.) You'll find it at archive.org/details/coloredpatriotso00nell.

I've used the story of the Marquis de Lafayette's farewell tour of America as a tow rope to take me through much of this history, (see Projectkin.org/lafayette). That story introduced me to James Armestead Lafayette.

I also didn't know anything about his story until I'd dug into Lafayette. I now better I understand the lyric reference to the "man on the inside" in the Yorktown scene in Hamilton.

So many stories, distorted and lost.