Change comes with uncertainty, and for those of us who white knuckled it through Trump’s first term as president, last week’s election results have invoked a sense of dread about the future. I’m not here to offer comfort or stoke fear about what may or may not happen when he assumes office, but I want to share an unusual strategy for coping with potential social upheaval: taking a walk in a cemetery.

This suggestion will come as no surprise to regular readers of The Silent Sod. For those of you who are new here, I hope I can convince you that visits to cemeteries, rather than being scary or depressing, can be incredibly life affirming if you’re intentional about connecting with the space. Below, I share some things that I look for on my walks that bring me solace.

Gaps in year of death between spouses

Spouses often share a gravestone, and one thing I naturally look for when I’m examining a couple’s marker is how far apart they died. At first, this can be upsetting, imagining one spouse having to go on without the other, but what can be intriguing about it is considering all the national or global events that transpired during the interval between their deaths.

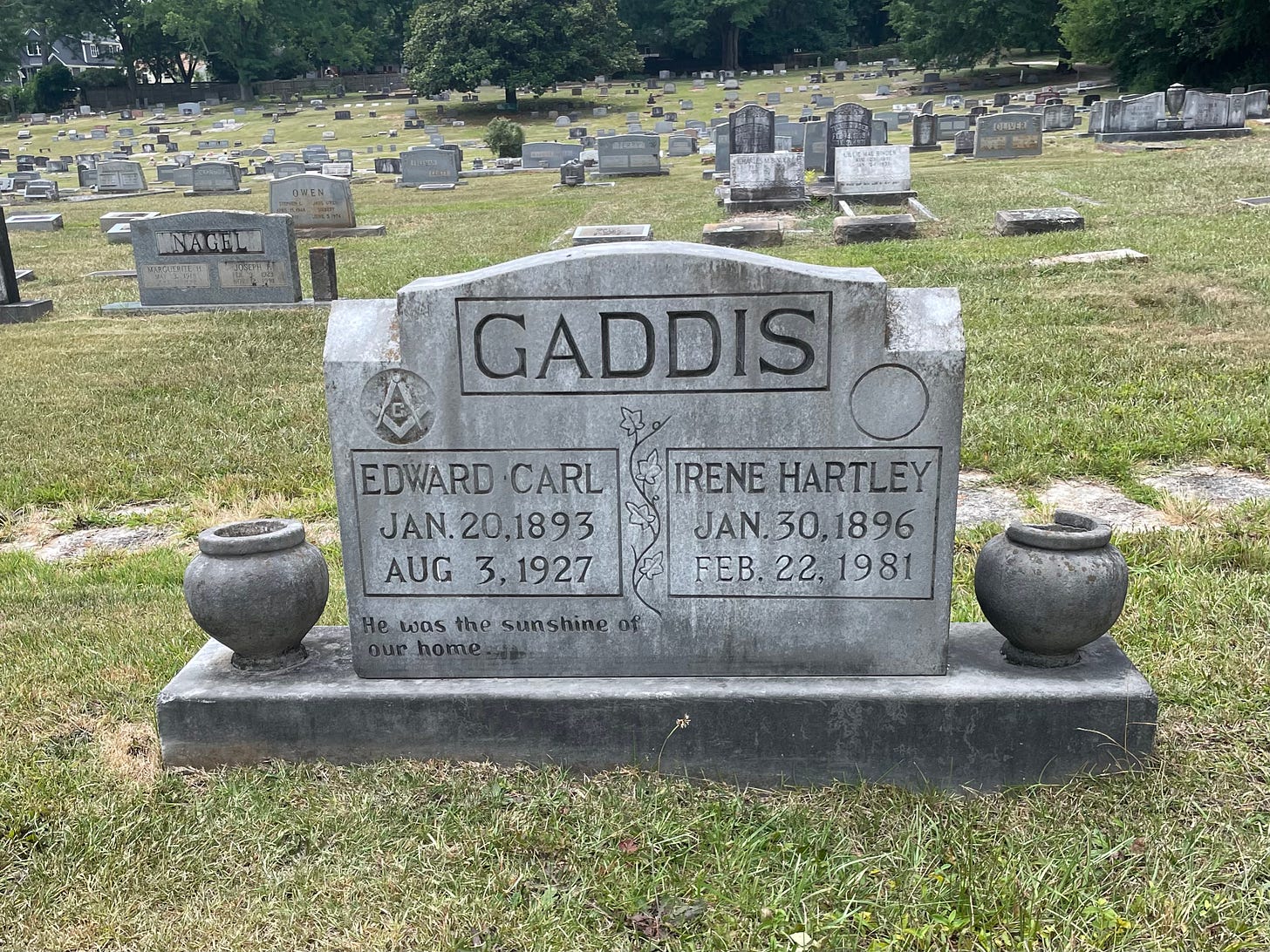

For example, take this couple buried at East View Cemetery in Atlanta where the husband died in 1927 and the wife in 1981 even though they were born only a few years apart.

In this case, the husband died in the middle of the Prohibition era, while the wife went on to live through the Great Depression, World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, Watergate, the moon landing, the rise of air travel and television, the launch of personal computers, and the election of Ronald Reagan. The world that she departed from was vastly different from the one that her husband left, and call me strange, but I find this “oddly comforting” because it underscores for me how little I know about what will happen in the future.

Ancient symbols that persist

Shortly after I trained to become a cemetery tour guide, I spent a summer in Paris where I successfully visited all the major collection areas of the Louvre Museum. Much of the ancient art there is funerary in nature, and I was particularly enamored of Greek steles (grave markers) that included figures shaking hands as a gesture of farewell.

Clasped hands are a common symbol on more contemporary graves as well and can symbolize matrimony, an earthly farewell, or a heavenly welcome according to Douglas Keister’s Stories in Stone: A Field Guide to Cemetery Symbolism and Iconography.

After my time spent at the Louvre in 2019, I learned more about ancient history by listening to lectures from The Great Courses while I fell asleep at night. The cultures I studied, like ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome, were far enough removed from my current reality that even when the content of the lessons was disturbing (e.g., Nero or Caligula’s reigns in Rome), I still managed to sleep. What studying ancient history taught me is that human lifespans are brief relative to the scope of human history but that any individual is subject to the history of their time.

What persists are things like family, love, mourning, and memorialization. The fact that we can go into a cemetery today and see the same symbols (e.g., hands clasped, crosses, urns, obelisks, etc.) that were in use thousands of years ago comforts me because it makes me feel connected not just to my ancestors but to people across cultures and throughout time.

History from the bottom up

History is often taught from the top down, focusing on rulers, conquerers, and those with political power. Cemeteries, in contrast, highlight regular people. If you look out across a cemetery lawn, you’re going to see tributes to those who inhabited that area in earlier eras. Their names might mean nothing to you, but these are people who lived full lives. What a cemetery promises is that all of our journeys end in the same way: death. Few of us will be remembered, many of us won’t. The meaning of our lives isn’t that which is assigned to us but that which we create.

A final thought

The future has always been uncertain. I woke up the day after the election much more frightened about that uncertainty. When I am experiencing anxiety, I try to use a technique I’ve learned from self-compassion meditation: acknowledging that I am not alone in feeling this way.

Walking through a cemetery, I always feel less alone.