One nice thing about having clearly defined passions is that when you meet new people you can connect over them. I tell pretty much everyone I encounter—my neighbors, my husband’s work colleagues, my hairstylist, other students in my improv classes, etc.—that I love cemeteries. A benefit of bringing this passion up is that people often recommend cemeteries to me. Such was the case with Hope Cemetery in Barre, Vermont, which I’d been recommended repeatedly since moving to the Northeast and finally checked out last August.

Granite City

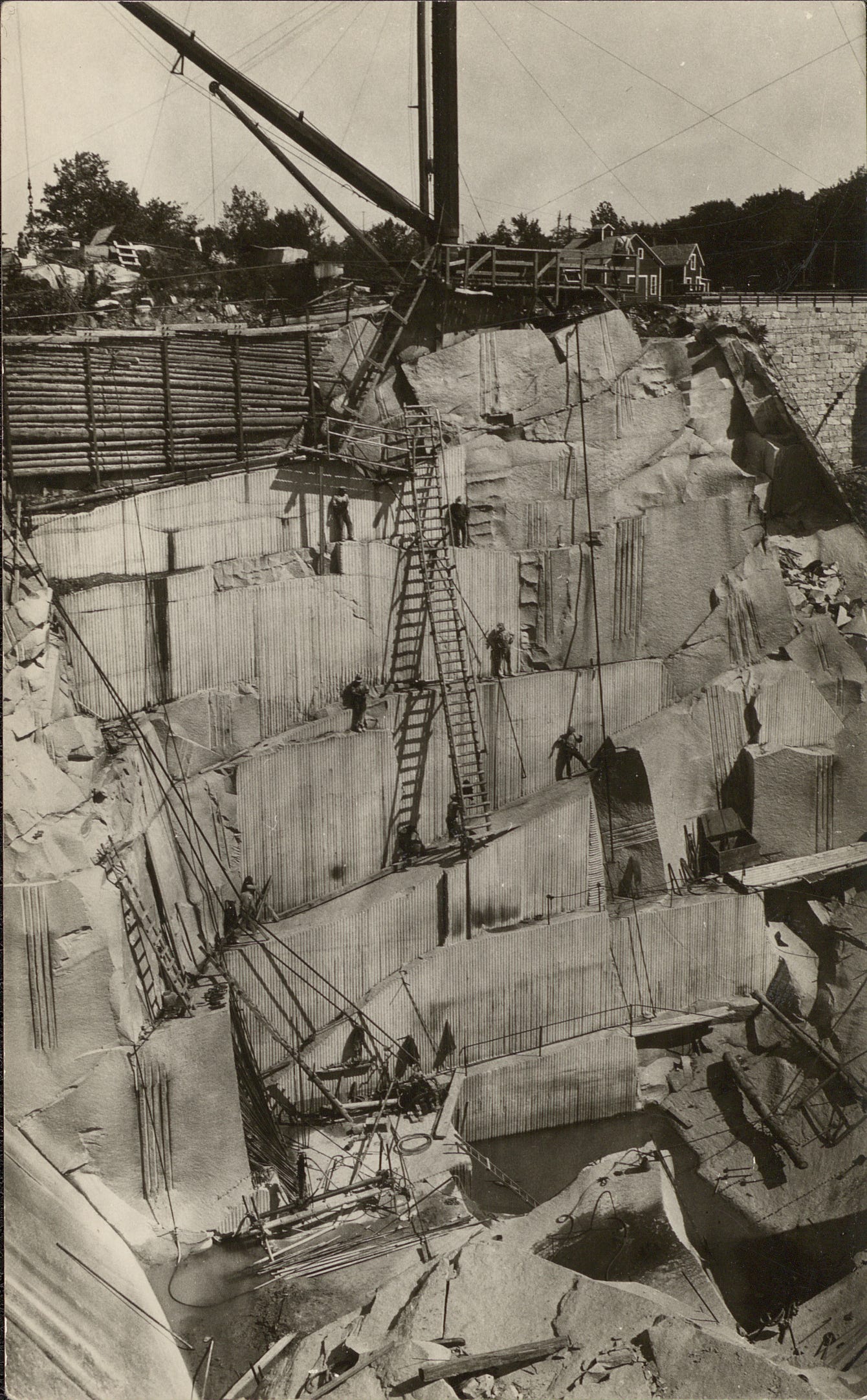

Hope Cemetery is located in Barre (pronounced Barry), Vermont, a city long known for its granite industry. Quarries were established in the early 19th century, and the rich supply of granite drew skilled stonecutters to the area, many of them Italian immigrants.

Uniformity in materials

If you spend a lot of time in historic cemeteries, one thing you’ll notice is that for the most part, the materials used to create monuments within a cemetery can vary substantially reflecting trends in popular materials (e.g, Colonial slate vs. Victorian marble vs. modern granite). Usually, the only time I see total uniformity in the type of stone used is when I’m in a military cemetery. At Hope Cemetery, though, almost all of the monuments, whether historic or more modern, are made of Barre granite, giving the cemetery a cohesive look.

The price of memory

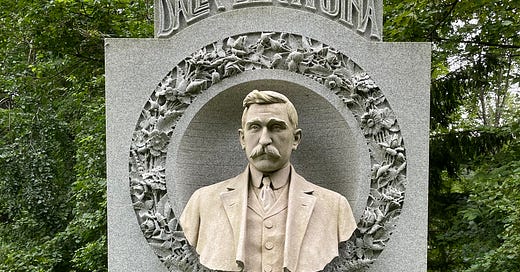

The most elaborate monuments I encountered at Hope Cemetery were tributes to stonecutters who died young. One was for Elia Corti, who was shot and killed at age thirty-three during an altercation between Barre’s anarchist and socialist groups. In addition to a lifelike rendering of the man himself, Corti’s gravestone includes a depiction of the tools of his trade.

While Corti’s premature death was due to violence, other Barre stonecutters met an early end because inhaling stone dust resulted in chronic conditions like silicosis. This also made it harder for them to recover from infectious diseases that impacted the lungs. For this reason, the 1918 flu hit Barre, Vermont, particularly hard with over 175 people dying within a single week. One victim of the epidemic was stone cutter Angelo Dalla Bernardina, who died at age forty-two. On his death certificate, lobar pneumonia is listed as the primary cause of death with influenza as a contributing disease.

One of the most moving sculptural pieces in the cemetery was the monument for Louis Brusa, who died of silicosis and tuberculosis in 1937. According to this article from Atlas Obscura, Brusa designed the monument himself and intended for it to send a message about the health hazards faced by stonecutters.

Since Barre was a significant source of granite for gravestones and memorials throughout the country, I have to wonder—what has been the human cost of erecting monuments meant to preserve memory and withstand time?

Love is strong as death

Right next to the Brusa monument in Hope Cemetery, you’ll find a monument that depicts a couple holding hands who appear to be sitting up in bed. Between them is a verse from Song of Songs (which you may remember from my post about the Carrie Tower at Brown University): “set me as a seal upon thine heart for love is strong as death.”

What beautiful stonework, and compelling stories., Plus, I love the old photos and the stories they tell!

What a wonderful piece! The monuments for the stonecutters are so moving, and I appreciate your research.