For my presidential picks so far, I’ve read a biography about each president that focuses on their whole life story. I’ve also enjoyed reading an additional book for each about a more focused topic. For Washington, it was about his travels throughout the country, and for Adams, it was the story of him being a lawyer for the soldiers involved in the Boston Massacre. For Jefferson, I decided to read The Hemingses of Monticello by Annette Gordon-Reed, a book that was suggested to me when I was learning about narratives of Blacks during the Revolutionary era.

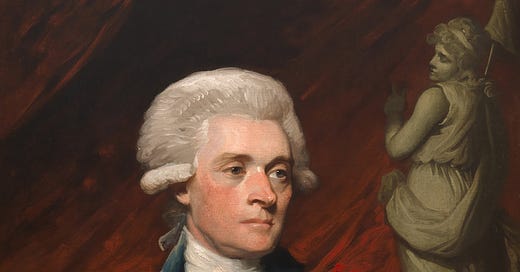

The book discusses the Hemings, who were the enslaved family that served Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson had a long term relationship with Sally Hemings, a woman who he enslaved. In reading both of the presidential picks about Jefferson, I learned about the irony of his work as the architect of American freedom as he himself held people in bondage. Jefferson acknowledged the evil of slavery, and at times in his political career, he did try to discuss the prospect of change, but ultimately he chose to leave the onus of abolition to a future generation.

Here are a few interesting things related to the life of Sally Hemings that I took away from reading:

Hemings was a half sister of Jefferson’s deceased wife.

When she was fourteen years old, Hemings traveled from America on a ship to Paris with Jefferson’s young daughter while Jefferson was serving as American Minister in France. At the time, Jefferson was legally obliged to register Hemings and her brother, who had already been with Jefferson in France, but he chose not to. According to the law in France at the time, Hemings was allowed to walk away from him in Paris to be free, but she chose to return with him to America, most likely due to his persuasion as well as the prospect of being alone in a different country.

Jefferson and Hemings had four children who survived into adulthood: Beverly, Harriet, Madison, and Eston. They were each eventually provided freedom from enslavement by Jefferson. Harriet was 21 when she was released and Beverly 24. Madison and Eston were released by Jefferson’s will in 1826.

Hemings' brother Robert bought his freedom from Jefferson, and her brother, James, had to train his brother, Peter, as a chef for three years in order to obtain his freedom from Jefferson. The book by Gordon-Reed also discusses the experience that James had training as a chef in Paris.

Though Jefferson tried to keep his relationship with Hemings hidden from society, apparently there was knowledge of it. In 1802, while Jefferson was president, a journalist named James T. Callendar made a point of noting the relationship and the fact that Jefferson fathered Hemings’ children. Callendar died in 1803, drowning in the James River after he had been seen in a drunken stupor.

Shannon LaNier, the sixth great grandson of Jefferson and Hemings, has written a book called Jefferson’s Children, which is an anthology of his travels to meet members of both sides of the Jefferson family. Apparently, he ran into some individuals who embraced his pursuit and others who rejected it. This is a book I would love to read in the future.

Jefferson and one of his greatest anxieties: slavery

In 1824, Jefferson received the Marquis de Lafayette, a Frenchman and a well known critic of slavery, at Monticello during Lafayette’s farewell tour of America.

Accompanying Lafayette on his tour and at Monticello was a woman named Frances Wright. She was originally from Scotland, and at the time of her visit to Monticello, she was speaking out against slavery and had proposed an idea to try to move the country toward freeing those in slavery.

A selection from an 1825 letter that Jefferson, at the age of eighty-two, wrote to Wright in reference to a community she founded to implement her idea demonstrates that though Jefferson had often thought about the evils of slavery he conceded that it was not going to be him or his generation of leaders that would put an end to it:

“I do not permit myself to take part in any new enterprises, even for bettering the condition of man, not even in the great one which is the subject of your letter, and which has been thro’ life that of my greatest anxieties. The march of events has not been such as to render its completion practicable within the limits of time alloted to me; and I leave its accomplishment as the work of another generation. and I am cheered when I see that on which it is devolved, taking it up with so much good will, and such mind engaged in its encouragement. The abolition of the evil is not impossible: it ought never therefore to be despaired of. Every plan should be adopted, every experiment tried, which may do something towards the ultimate object. that which you propose is well worthy of trial. It has succeeded with certain portions of our white brethren, under the care of a Rapp and an Owen; and why may it not succeed with the man of color?”

I learned that this woman Frances Wright is buried in Spring Grove Cemetery in Cincinnati, Ohio, so I decided to learn more about what these experiments she was proposing involved and pay a visit to her grave. In the next Silent Sod, I will discuss what I found out about Frances Wright and the community that she founded as an attempt to end slavery in America.

Sources:

https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/98-01-02-5449

https://www.monticello.org/research-education/thomas-jefferson-encyclopedia/frances-wright/

Jefferson: Architect of American Liberty, John Boles, Perseus Books, 2017.

The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family, Annette Gordon-Reed, W. W. Norton and Company, September 8, 2009.

I'm excited to continue looking at the issue of problems inherited from earlier generations and how they are addressed, especially with regards to slavery.

Interesting books about Thomas Jefferson and i am glad that the effort was made to tell the story of the Hemingses.