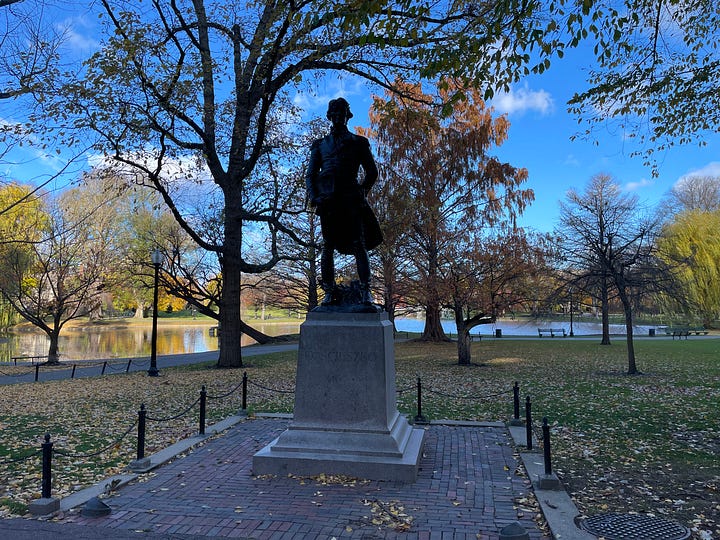

A beautiful Sunday morning, late autumn, I was strolling through Boston’s Public Garden, trying to soak in a little history before brunch. A statue of Charles Sumner set against stunning yellow foliage caught my eye. Click.

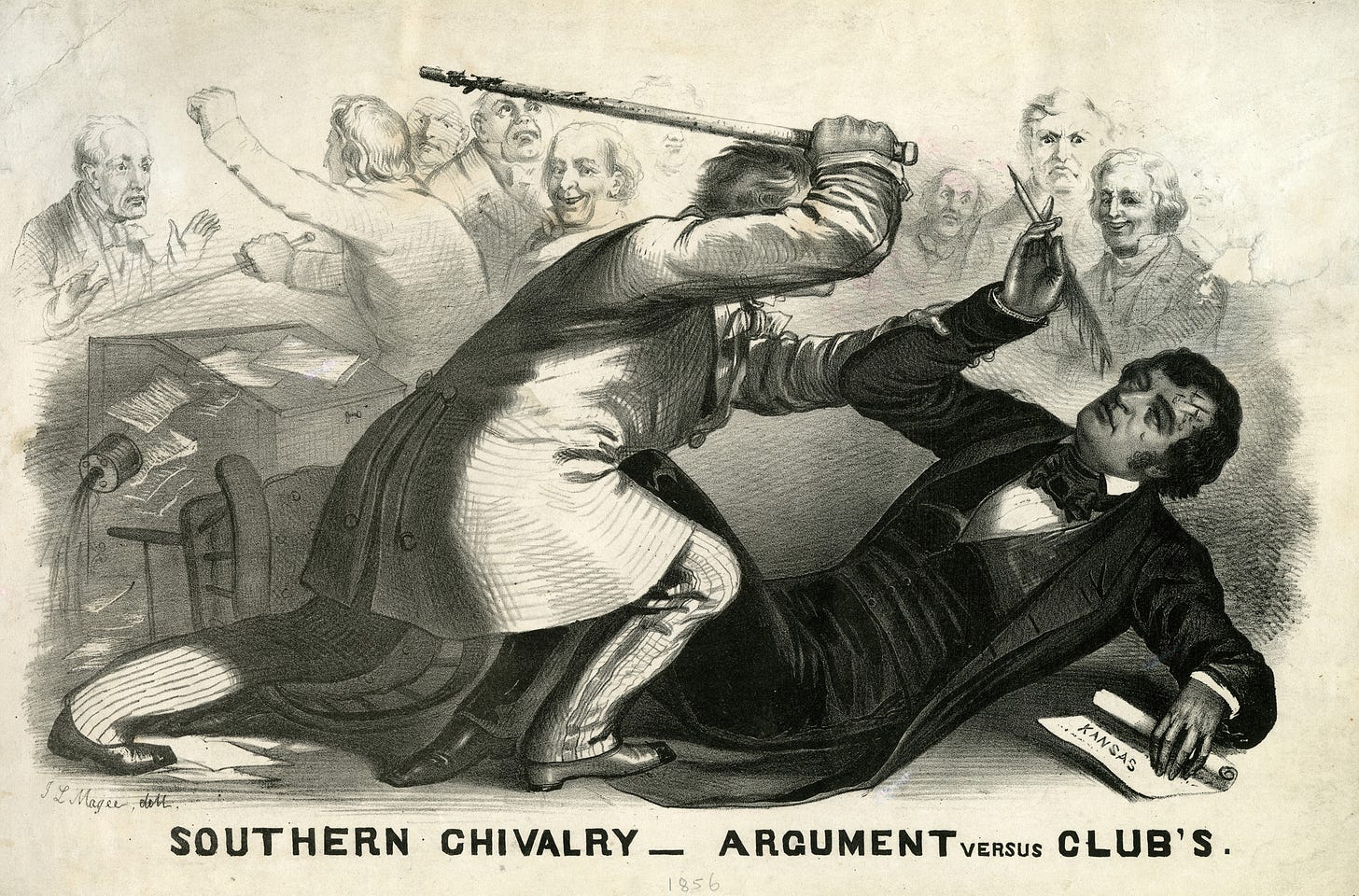

I recognized Sumner’s name, but it wouldn’t be until I looked him up later that I remembered what the Civil War era Massachusetts senator was known for—having almost been beaten to death in the Senate chamber by Representative Preston Brooks of South Carolina. Sumner was an ardent abolitionist while Brooks was in support of slavery and its expansion into the Kansas territory.

Along the same road, right past Sumner, I came across two more statues of men: Thomas Cass and Tadeusz Kościuszko, colonels in the Civil War and Revolutionary War respectively. Both were born outside of America yet distinguished themselves in service to the country. The light wasn’t hitting either of them right, but that didn’t stop me. Click. Click.

I walked a little further and happened upon the most elaborate monument yet: a bronze statue of Wendell Phillips set atop a pink granite pedestal and in front of a pink granite wall. The statue was carved by Daniel Chester French, who is most famous for sculpting the seated statue of Abraham Lincoln at the Lincoln Memorial. An epitaph at the top of the Phillips monument read “whether in chains or in laurels liberty knows nothing but victories.” Below, Phillips was described as a “prophet of liberty” and “champion of the slave.” I had to wash out the background of the picture to capture the details of the statue and the engravings, but this could be done relatively easy with my phone camera. Click.

Assessing abolitionists

Maybe it was because it was the fourth statue in a row of a white man and I have a problem with how memorialization can reinforce the patriarchy, but, knowing nothing about him other than a vague recollection of his name, I wasn’t convinced that Wendell Phillips was as great as he was being made out to be on this memorial.

See, I’ve learned recently that not all abolitionists were invested in both emancipating the enslaved and granting them citizenship. In general, the title was used in reference to anyone who wanted to see slavery end, but some so-called abolitionists aligned themselves with Southern slaveholders via the American Colonization Society with a goal to expatriate both free Blacks and enslaved Blacks, whose freedom would be purchased, to places like Liberia and Haiti. The basic premise of this organization was that given the history of slavery in America white and Black people could not coexist with equal rights.

When you want to assess the values of someone who is called an abolitionist, here are some questions you can ask about them:

How quickly did they want slavery to end?

Did they think slave owners should be compensated for their loss of property?

Did they think the formerly enslaved should be given land?

Did they think the formerly enslaved should become American citizens and be given rights or that they be sent to somewhere else like Liberia or Haiti?

How did their perspectives shift or change over time?

The Anti-Slavery Society versus the Colonization Society

I first learned about the American Colonization Society when I came across this intriguing incident in the Amherst College timeline:

“July 19, 1834: Students form an Anti-Slavery Society, which clashes with the Colonization Society. The faculty requests that both societies disband. The Colonization Society complies in summer 1834, but the Anti-Slavery Society protests and persists. In February 1835, the faculty declares that ‘in the present agitated state of the public mind, it is inexpedient to keep up any organization under the name of anti-slavery, colonization, or the like in our literary and theological institutions.’ The Anti-Slavery Society thereafter meets in secret.

At first, I thought the Colonization Society was a group of students who wanted America to continue to expand its empire and was confused about exactly what their issue was with the Anti-Slavery Society. Then, I attended a lecture about Amherst College’s ties to slavery given by Andy Hammann and learned that the college’s Colonization Society was tied to the American Colonization Society. I believe that the fundamental disagreement between the two college groups was whether Black people should be allowed to live freely in America. The faculty wanted to suppress the conflict because they didn’t want to offend wealthy Southern slaveholders who sent their sons to the college.

Wendell Phillips, the real deal

With this history in mind, I dug into the biographical information about Wendell Phillips to see whether he had ties to the American Colonization Society. What I found indicated that Wendell Phillips was an authentic abolitionist, and although I would phrase his descriptors slightly differently today, he was indeed a “prophet of liberty” and “champion of the enslaved.”

Phillips’ embrace of abolitionism reads like the story of St. Paul’s conversion on the road to Damascus. Phillips was born to a wealthy family in Boston, attended Harvard, and had a promising career in law when in 1835 he witnessed a mob try to lynch the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison in Boston. Phillips became a follower of Garrison, who in 1829-1830 had rejected the American Colonization Society and in 1833 had founded the Anti-Slavery Society.

By aligning himself with Garrison, a radical abolitionist, Wendell Phillips was forced to give up his law practice, social connections, and the comfortable life he had known. He became a well known orator on the subject of abolition which made him the target of threats. In a 1915 Boston Globe article describing the dedication of the Wendell Phillips memorial, I found these lines from a speech given by William D. Brigham particularly compelling:

“We do well to honor his memory—to remember that when friends forsook him, when his own family turned from him, and when the church of the living God, which should have led in the conflict, was either indifferent or hostile, he never wavered in his purpose that slavery should be abolished.

I think it is impressive to remember how few persons there really were who furnished the inspiration, did the work, risked their lives, to free the slave—Phillips, Garrison, Sumner, Andrew, Beecher, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Whittier, Theodore Parker, Abraham Lincoln, and Julia Ward Howe.” -speech by William Brigham quoted in The Boston Globe. Boston, Massachusetts. Jul 6, 1915, p.20.

How about Frederick Douglass?

One thing that struck me about Brigham’s list of persons willing to sacrifice themselves for the cause of abolitionism was that it excluded notable Black abolitionists like Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, and Sojourner Truth. I think Phillips himself might have taken exception to this. He was a friend of Frederick Douglass, and wrote a letter to him that was included in Douglass’s Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave where he expressed fear for Douglass’s safety in publishing his account:

“After all, I shall read your book with trembling for you.”

“I am free to say that, in your place, I should throw the MS [manuscript] in the fire.”

-quotes from “Letter from Wendell Phillips Esq.” that appears in Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave

Beyond Emancipation

Phillips was described as a “prophet of liberty,” and it’s true that even beyond the abolishment of slavery, he stayed committed to the cause of freedom his whole life. After the Civil War, he supported newly emancipated slaves being given the right to vote. He also argued that Indigenous groups (Native Americans) should being granted citizenship. He also advocated on behalf of the women’s suffrage movement.

Back of every great work

Wendell Phillips embrace of abolitionism was no doubt inspired by the attempted lynching of William Lloyd Garrison that he witnessed and, a couple years later, the assassination of Elijah Lovejoy, another abolitionist.

An additional source of inspiration, though, was his wife, Ann Terry Greene Phillips, who he was married to for forty-six years. Her contributions were documented by William Lloyd Garrison’s son, Francis Jackson Garrison, in Ann Phillips, Wife of Wendell Phillips: A Memorial Sketch.

While we have a Daniel Chester French statue of Wendell Phillips in Boston’s Public Garden, this is the surviving image of Ann Phillips:

Her relative obscurity reminds me of the memorial tablet recognizing Emily Warren Roebling’s contributions to the Brooklyn Bridge: “back of every great work we can find the self-sacrificing devotion of a woman.”

So, in conclusion, Wendell Phillips is cool, but I’m still upset about the patriarchy.

Sources:

https://www.nps.gov/people/wendell-phillips.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wendell_Phillips

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Lloyd_Garrison

“Pay Loving Tribute to Wendell Phillips.” The Boston Globe. Boston, Massachusetts. Jul 6, 1915, p. 20.

Douglass, F., Garrison, W. L. (1849). Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. United States: Anti-Slavery Office.

Boston. City Council. (1916) Exercises at the dedication of the statue of Wendell Phillips, July 5. City of Boston, Printing department. [Pdf] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/17001518/.

Garrison, F. J. (1886). Ann Phillips, Wife of Wendell Phillips: A Memorial Sketch. United States: private circulation.

Great article! I wonder why they blacked out her face on that drawing!!