William Finch & Daffodils Pt. 1

A white writer interrogates the stories she tells about Black cemetery residents

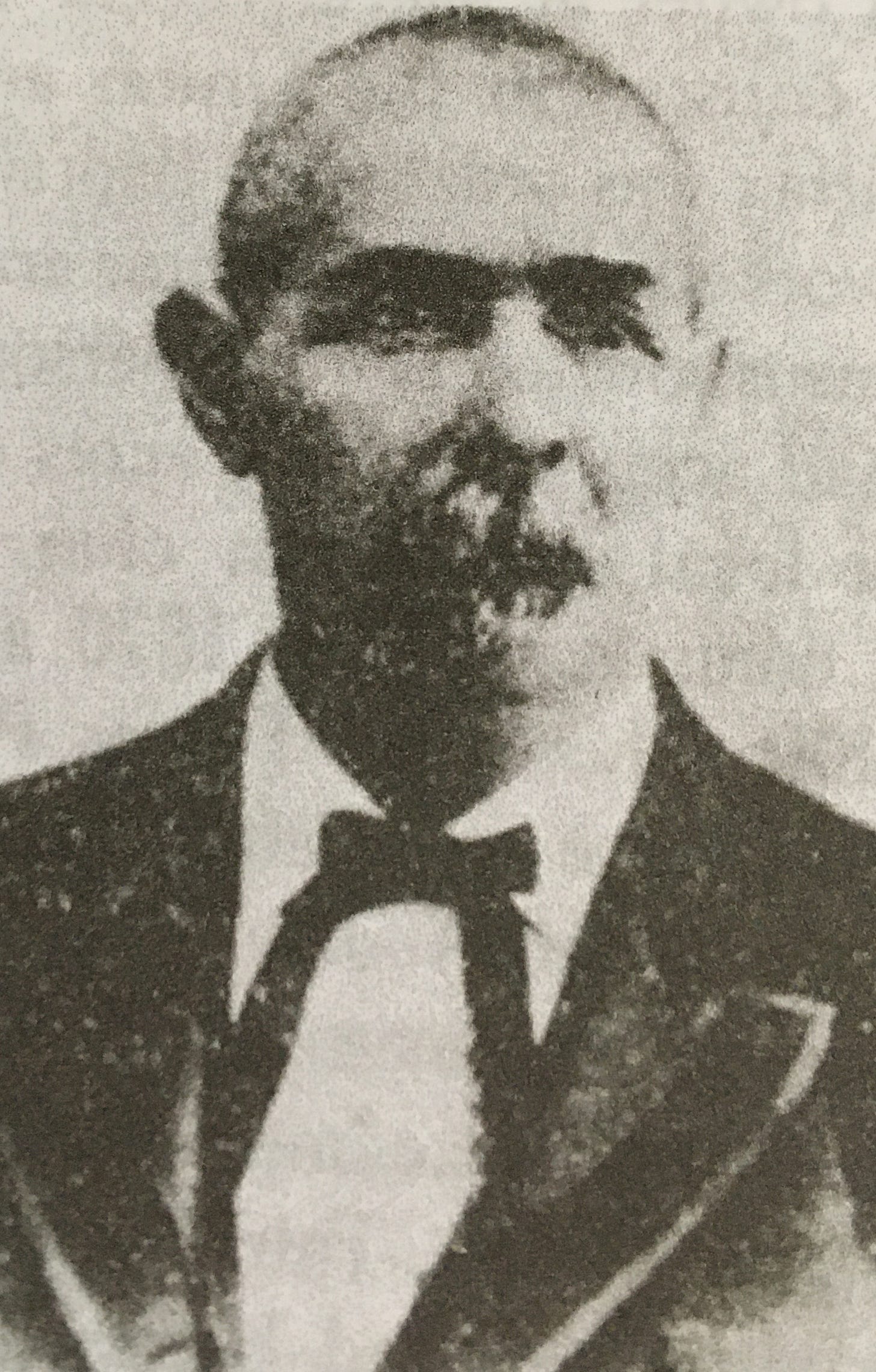

Some of the earliest daffodils in Atlanta’s Oakland Cemetery bloom in front of the grave of William Finch, a tailor and politician who was a leading figure in the city’s Black community following the Civil War. His story was one I learned when I trained to be a guide for the We Shall Overcome tour at the cemetery. I loved telling it because it allowed me to give an overview of about a hundred and twenty years of Atlanta’s political history in a single stop.

As I learned for the tour, William Finch was born enslaved and trained to be a tailor as a young man. During the Civil War, he accompanied his enslaver’s son to the battlefront, but he showed his true affiliation at the end of the war when he sewed an American flag and presented it to Union troops. During Reconstruction, he was elected to the city council in Atlanta and served one term. This was in 1870, and there wouldn’t be another Black person elected to a city office until 1953. Atlanta wouldn’t elect it’s first Black mayor, Maynard Jackson, who is also buried at the cemetery, until 1973.

Much is revealed by this story: (1) the fact that enslaved people were sent to the war, not to fight, but to serve their enslavers, (2) the brief time during Reconstruction when newly freed Blacks were enfranchised and elected as representatives, (3) the decades of Jim Crow bullsh*t that followed which kept Black people out of office (e.g., white only primaries). Then, to me, the icing on the cake is Finch’s act of resistance, presenting the American flag to the Union troops who would have enforced the Emancipation Proclamation in the areas they occupied during the war.

Recently, I saw the movie American Fiction (2023) which takes as its premise that white power holders in the publishing industry and white audiences relish stories of Black struggle. The movie is based on Percival Everett’s novel Erasure (2001) that critiques the commercial success of books like Sapphire’s Push (1996), which the film Precious (2009) was based on.

I couldn’t emotionally handle the trailer for Precious. I’d sob every time it came on, and I definitely did not want to see the movie. So I’d say my reaction to that film at least wasn’t the same as the white people portrayed in American Fiction.

But there’s something about how I enjoy telling the story of William Finch that sits funny with me sometimes.

Near William Finch’s grave, in the Historic African American section of the cemetery, is a marker for a man referred to on his headstone as “Uncle Bill” Wainald Yopp. I’ve never learned about him on a tour, but his stone caught my eye one day because, in addition to his name and years of birth and death, it mentions that he was a historic aide to Thomas McCall Yopp, Capt. CSA-CSN. This position of aide seems like the role William Finch had during the war.

When I looked up Bill Yopp on my #1 internet rabbit hole, newspapers.com, I found that although the two men’s involvement in the war sounded similar, Yopp’s attitude in the years following the war differed from what I had learned of Finch’s, at least allegedly according to major news outlets of the time which would have been run by white publishers. What I learned about Yopp didn’t give me the same sense of joy that Finch’s story did. In fact, I felt the opposite.

While I delighted in the idea of William Finch presenting Union troops with an American flag, I was somewhat horrified to learn that Bill Yopp was recognized later in life for fundraising for veterans in the Confederate Soldiers’ Home. Sources indicate Yopp lived in the home himself, and his stone in Oakland may be an cenotaph, because there is also a marker for him in the Marietta Confederate Cemetery.

Over the next several weeks, in this Photo-Synthesis series called William Finch & Daffodils, I’m going to examine how the stories of these two men have been told over time as well as analyze my reactions to them. I’ll compare their obituaries, printed at the time of their deaths, and I’ll share news articles about William Finch that reveal more facets to his life than the narrative I’ve shared as a tour guide. I’m also going to see if anything can be gleaned by examining an account of the war written by a white woman, Eliza Frances Andrews, whose father’s home William Finch lived in while he was enslaved (it’s not clear to me who his enslaver was at the time).

I won’t lie, taking on this discussion is daunting, but it’s one of the main reasons I started this Substack. If you have thoughts, I hope you’ll leave comments or reach out to me directly.

True to the premise of Photo-Synthesis, I’ll also be including a flower photo with these posts. Starting with…

William Finch’s Daffodils

The shape of his gravestone represents a key to heaven.