Boyrereau Brinch: a freedom fight within a freedom fight

The American Revolution from different perspectives Pt. 2

During the Revolutionary Era, the promise of freedom was central to those fighting for the independence of the American colonies from the British Empire. It is ironic that some of those who fought this battle were themselves fighting for freedom from a different tyrant: slavery. I have recently become interested in reading the first hand accounts of Blacks who lived in the Revolutionary period because I think that it is important to learn their perspective and point of view in understanding the history of the country as a whole.

Boyrereau Brinch, nicknamed Jeffrey Brace, was born around 1742 in West Africa. Due to his blindness, he orally relayed the account of his life to Benjamin Franklin Prentiss, a white antislavery lawyer. Prentiss wrote the document, and it was published in 1810 by Harry Whitney. Prentiss at the time was a young lawyer and Brinch an elderly man. More is known about Brinch than is known about Prentiss, and it is a mystery how they came to know each other and what made him decide to write his story.1 The account is titled The Blind African Slave, or Memoirs of Boyrereau Brinch, Nick-named Jeffrey Brace.2 It discusses his kidnapping in Africa to be sold into slavery, his years of slavery, his service in both the French and Indian War and the American Revolutionary War, and his emancipation after his service in the Revolutionary War.

The Kidnapping

At the age of sixteen years, Brinch reported going with a group to bathe in the Niger, which he characterized as, “a useful as well as pleasing amusement.” He described the experience as enjoyable, and when he and the group came back to dress and return home, the bad turn of their life began. He stated, “But Lo! when we had passed the borders and entered the body thereof, to our utter astonishment and dismay, instead of pursuers we found ourselves waylayed by thirty or forty more of the same pale race of white Vultures, whom to pass was impossible, we attempted without deliberation to force their ranks. But alas! we were unsuccessful, eleven out of fourteen were made captives, bound instantly, and notwithstanding our unintelligible intreaties, cries & lamentations, were hurried to their boat, and within five minutes were on board, gagged, and carried down the stream like a sluice; fastened down in the boat with cramped jaws, added to a horrid stench occasioned by filth and stinking fish; while all were groaning, crying and praying, but poor creatures to no effect.”3

Life in Slavery

The descriptions of Brinch of his life in enslavement are disturbing. He spoke of families witnessing the sexual assault of their daughters and wives as well as an experience he had of getting beaten simply because he threw up. A white woman who witnessed this attempted to speak up on behalf of Brinch for this aggression, but she was threatened with a whip. A poem that Brinch referred to spoke frankly of the treatment the enslaved endured as well as hope for eternal justice:

Beneath a tyrants harsh command,

He wears away his youthful prime

Far distant from his native land

A stranger in a foreign clime:

No pleasing thoughts his mind employ,

A poor dejected Negro Boy.But he who walks upon the wind,

Whose voice in thunder's heard on high,

Who doth the raging tempest bind,

Or wing the light'ning thro' the sky,

In his own time will soon destroy

Th' oppressors of the Negro Boy.-“The Negro Boy,” a popular anti-slavery song published in Washington D.C. in 1802, quoted in Brinch’s memoirs.4

Literacy and wartime

One event proved to be life changing for Brinch. His female enslaver, a widow named Mary Styles, taught Brinch how to read. He was an avid reader of the Bible and throughout the account several Biblical quotes are provided. His literacy was a valued part of his life and identity. Of his learning to read he stated, “accordingly she with intentions as good and pure as virtue itself, taught me to read and speak the English language. She was indefatigable until I could read in the Bible and expound the scriptures, in the meantime she taught me the prayer usually communicated to children, and some general principles of the christian religion. Both day and night she most kindly taught me, by which I am enabled to enjoy the light of the gospel.”5

Of his service during his enslavement in the Revolutionary War, he stated, “I also entered the banners of freedom. Alas! Poor African Slave, to liberate freemen, my tyrants. I had contemplated going to Barbados to avenge myself and my country, in which I justified myself by Sampson’s prayer, when he prayed God to give him strength that he might avenge himself upon the Philistines, and God gave him the strength he prayed for.”6

Liberation

After the Revolutionary War, Brinch returned to his enslaver in Connecticut who agreed to his freedom resulting from his service in the war. He decided to move to Massachusetts and afterwards settled in the town of Poltney in Vermont, of which he is said to be the first African American resident. Regarding his freedom in Vermont, he stated, “here I enjoyed the pleasures of a freeman; my food was sweet, my labor pleasure: and one bright gleam of life seemed to shine upon me.”7

Though his story did end well, in the accounts I have read regarding the prospect of freedom for Black veterans of the Revolution, it was not always the case that the enslavers were willing to cooperate with this process and often individuals had to fight further for their independence. I was glad to read that in Brinch’s case he was able to obtain his freedom without this additional setback.

Obituary and Conclusions

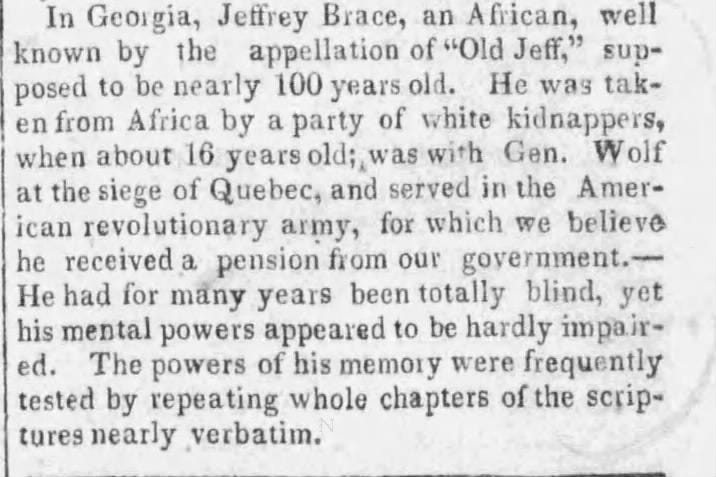

I was able to find the obituary of Boyrereau Brinch on newspapers.com, which I believe speaks to the character of this man:

To me, the words of Brinch are an honest and direct statement to the morals of American society during the Revolutionary War. I think it is important to understand the story of Blacks throughout the development of America, including those in the Revolutionary period in order to acknowledge the brave individuals whose actions pushed the notion of freedom in America to the height that it has come to be. And also to consider: if we were to read about our own times in the future, are we truly fulfilling the notion of freedom?

The American Revolution Institute. “The Heroic Jeffrey Brace.” 25 September 2020. https://www.americanrevolutioninstitute.org/the-heroic-jeffrey-brace/

Brinch, Boyrereau. Prentiss, Benjamin F. The Blind African Slave, or Memoirs of Boyrereau Brinch, Nick-named Jeffrey Brace. Printed by Harry Whitney. 1810. https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/brinch/brinch.html

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

This is reminding me of Frederick Douglass's speech "What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?" I recommend reading it: https://www.google.com/books/edition/Oration_Delivered_in_Corinthian_Hall_Roc/1glyAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&printsec=frontcover