In my last post, I discussed how I came across the grave of an individual named Henry Boyd. This week, I will discuss what I learned about his life and legacy.

Early life

Henry Boyd was born in 1802 in Carlisle, Kentucky. He was born into slavery. His mother was enslaved and was from Virginia, and his father was a white man from Scotland. As a teenager, Boyd was hired out to work at a place, Kanawha Salt Works, in what is now West Virginia. During his time there, he had his first interactions with both enslaved and free Blacks from other states, including some from Cincinnati, Ohio. He later worked as an apprentice for a carpenter and was able to earn extra money. Eventually, he purchased his freedom and arrived in Cincinnati in either 1825 or 1826.1

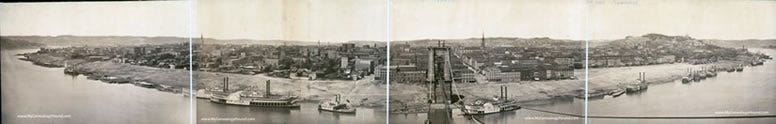

Cincinnati, Ohio

Though slavery was illegal in Cincinnati at the time Boyd arrived, there was a great deal of hostility toward free Blacks and sympathy toward the South, especially from white, primarily Irish immigrants who feared losing jobs to the newly freed Black population.

One incident in Cincinnati that occurred three years after the Boyd’s arrival would exemplify this. Between August 15th and 22nd of 1829, a mob of 200-300 ethnic whites attacked the Black areas of the First Ward of Cincinnati. The aim of the mob was to push Blacks out of the city. Between 460 to 2,000 people fled to Canada as a result of the riots, but some Blacks stayed and started to organize. The riots were a topic of discussion at a gathering of Black leaders in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1830.2

Henry Boyd remained in Cincinnati after the riots. It is noted that he had difficulty finding jobs that used his skill in carpentry, but he was able to start making money by unloading cargo ships along the Ohio River where many African Americans and Irish found employment. Boyd eventually found himself in situations where his carpentry skills could be used, and by word of mouth, he was able to obtain carpentry jobs by contract. With the income he made, he was able to purchase not only his own workshop for woodworking but the freedom of his brother and sister.3

Family in Cincinnati

According to census records Henry was married to a widowed woman in Cincinnati named Kesiah Boyd. Kesiah Boyd is described as “mulatto” on the 1850 and 1860 census records. He and his wife were married for thirty-six years. They were introduced by his mother-in-law, Emma Laws.

He also had a stepdaughter, Sarah James, through Kesiah Boyd as well as his own daughter, Maria, who he lived with at his time of death.4

Innovation

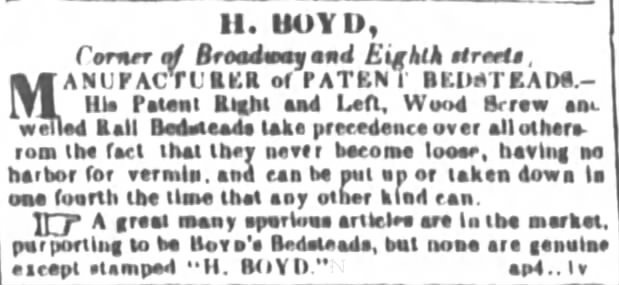

“Innovative” is an adjective that I believe fits perfectly with the life of Henry Boyd. In his carpentry business, he created a bed frame called the “Henry Boyd Bedstead” which apparently was a step up from the bed frames of the time, allowing for more sturdiness. An article in The Cincinnati Enquirer dated November 27, 1885 reads:

“Henry Boyd, patent bedsteads, on the corner of Eighth and Broadway, in four words tells the history of one of the most intelligent colored citizens, who made a large fortune with a bedstead of his own invention, but lost it all by embarking in other enterprises. The Boyd patent being iron fastenings for the rails in the head and footboards, doing away with the old fashioned screw-rails and rope cordings. It was also a mortal enemy of the innocent little things called bed-bugs.”5

One of these bedsteads is still in use today at the Golden Lamb Inn in Lebanon, Ohio. It is located in the room named after DeWitt Clinton, an American politician and naturalist.

The bedstead was not the only example of Boyd’s innovation. His business was notable in that it was racially integrated, employing both Blacks and whites. His white workforce was mostly Irish, which is somewhat ironic since this population feared newly freed Blacks would take away their jobs not provide them jobs.

Here is one other fact I learned about Boyd that demonstrates his forward thinking. During one of several outbreaks of cholera Boyd lived through in Cincinnati, it was noted in a news article that he suggested boiling water as a remedy. This was before it was discovered that water was the mode by which the disease was spread.

A Legacy of Freedom

In my previous post, I mentioned I found it somewhat shocking that in our brief time researching for The Silent Sod we’ve encountered the story of Boyd in two unrelated spots: the Golden Lamb Inn and Spring Grove Cemetery.

The day I discovered Boyd’s grave in Spring Grove, I first happened upon the grave of Alphonso Taft. It seems these men had a connection—both of them were fighting for the cause of abolition in pre-Civil War Cincinnati.

Boyd was known to play an active role in the Underground Railroad as a conductor. It is believed that his home may have been the first on the stop for people escaping slavery once they made it across the Ohio River.6 Given this fact, we may never know just how far his legacy of freedom plays out today.

Later in life, Boyd was also known to participate in local politics, specifically the Republican party’s backing of Ulysses S. Grant.7 It is interesting to consider if Henry Boyd ever crossed paths with Alphonso Taft given the latter was a distinguished member of the Republican party in Cincinnati.

According to Spring Grove burial records, Henry Boyd passed away on March 1, 1886, about one month short of his eighty-fourth birthday. His cause of death was listed as old age.

His obituary published in The Cincinnati Enquirer reads, “Henry Boyd, 84, an old Cincinnatian who was in the early days a manufacturer of bedsteads, died yesterday.” Oddly, his obituary is one of two that appears in section titled “Two German Pioneers Gone.” The other obituary is for a man named William Pieper, whose remains were shipped from Germany for burial at Spring Grove.8

Henry Boyd was buried along with his wife, Kesiah, in a plot owned by his step daughter, Sarah James. Henry Boyd’s grave was noted to be unmarked for many years. Noticing that Boyd’s current marker appears to be built in recent years, I reached out to Spring Grove Cemetery to ask if someone had donated to create the headstone. They responded that Spring Grove themselves, with the approval of their president, donated his marker.

Conclusion

Reading about the story of Henry Boyd speaks both to the hardships faced as well as the progress made by Americans who came before us in securing basic rights such as employment. Henry Boyd gained his freedom from slavery and walked into a different set of societal standards that attempted to put further limitations on his life. However, he pushed through with his actions and not only survived but thrived and used his surplus to the benefit of others. I am glad that the Golden Lamb and Spring Grove Cemetery are taking steps to keep his story alive.

https://blog.lostartpress.com/2022/03/13/henry-boyd-a-remarkable-life/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cincinnati_riots_of_1829#:~:text=The%20Cincinnati%20race%20riots%20of,in%20the%20preceding%20three%20years.

https://nkytribune.com/2019/02/our-rich-history-henry-boyd-once-a-slave-became-a-prominent-african-american-furniture-maker/

https://blog.lostartpress.com/2022/03/13/henry-boyd-a-remarkable-life/

The Cincinnati Enquirer. Sign Board Lore: How the Custom of Signs Denoting Businesses Originated. November 27, 1885.

https://nkytribune.com/2019/02/our-rich-history-henry-boyd-once-a-slave-became-a-prominent-african-american-furniture-maker/

https://blog.lostartpress.com/2022/03/13/henry-boyd-a-remarkable-life/

The Cincinnati Enquirer. Two German Pioneers Gone. March 3, 1886.

Very inspiring story. I am glad you stumbled on it.