John Quincy Adams: writings from a young future president.

The American Revolution from different perspectives Pt. 3

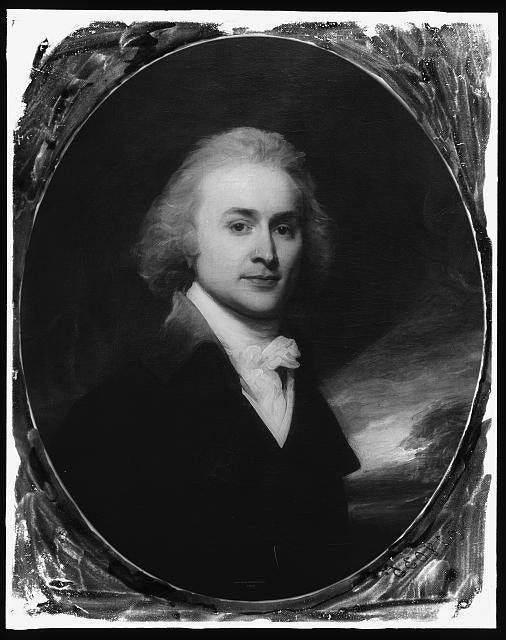

The perspectives discussed so far in this series on the American Revolution have been from individuals whose stories are not widely known. For Pt. 3, we will discuss the account of an individual who was the sixth president of the United States, John Quincy Adams. Though written by a public figure, I consider the account to be a unique viewpoint of the Revolutionary Era because Adams was in his youth, accompanying his father on his work negotiating on behalf of the American colonies in Europe, when he wrote it.

On Leaving for Europe, November 12th, 1779

John Quincy Adams, the son of the second president John Adams, left for Europe from Boston, Massachusetts with his father at the age of twelve. Here is the entry from his diary, which has been digitized by the Primary Source Cooperative at the Massachusetts Historical Society:

“Friday 12th this Morning at about 11 o clock I took leave of my Mamma, my Sister, & Brother Tommy, and went to Boston with Mr Thaxter, in order to go on board the Frigate the Sensible of twelve Pounders. we arrived at Boston at about 1 o clock; dined at my uncle smiths’, we expected to go on board in the afternoon but We could not conveniently—till tomorrow.”1

Once he arrived, John Quincy Adams spent several years in Europe and kept a journal of his times and experiences.

On Politics August 10 and 11, 1783

There are a couple journal entries that I thought were humorous given that he went on to become president and a member of the House of Representatives at a later time and devoted his entire life to politics.

“This morning, at about 10 o’clock, I accompanied my Father to Passy, to see Dr: Franklin whom I knew already, and Mr: Jay, the american Minister at Madrid, whom I had never seen before; they were at breakfast and had a great deal of Company. Mr: Jay and my Father took a walk in the Garden and had a Conversation upon politicks, which, is of no Necessity here.”2

“This morning Mr. Hartley the British Minister for making Peace, came to pay a visit to my Father. but as he was out he desired to see me. I had some Conversation with him. he says he hopes the Peace will be soon signed. In the afternoon I went with my Father to Passy, and saw there Dr: Franklin and Mr: and Mrs. Jay. I also renewed my acquaintance with young Mr: Bache.

We went at the same time to see the Abbés Chalut and Arnauld two gentlemen of letters, with whom my Father has been familiarly acquainted ever since his first arrival in Europe. we found with them the Abbé de Mably, famous for being the author of a work entitled Le Droit public de l’Europe; and of another entitled principes des Negociations. and the Abbé le Monnier who has given to the world an elegant French Translation of Terence’s Comedies. As the general Turn of the Conversation was upon Politicks; there was nothing in it, necessary to be transcribed here.”3

On The Treaty of Paris September 3, 1783

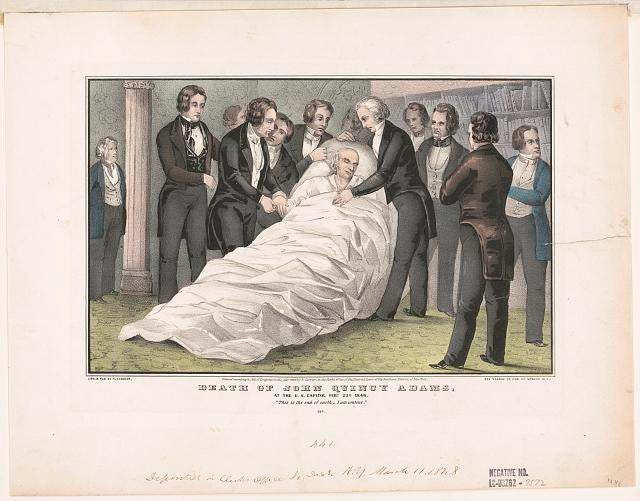

I had read that at the age of sixteen he served as secretary for his father when he signed the Treaty of Paris, the treaty in which the English acknowledged American independence. When I got to the five worded journal entry, I found that Adams did not have much prolific insight to share on that matter:

“Signature of the Definitive Treaty”4

On Flying Globes August 27, 1783

An event that the young Adams did have much to say about was witnessing the first public experiment of hot air balloons in Paris, which at the time he referred to as flying globes:

“This forenoon I went to see the Pictures which are exposed to view in the Gallery of the Louvre; there are some good paintings there amongst a great number of indifferent ones. after dinner I went to see the experiment, of the flying globe. A Mr: Montgolfier of late has discovered that, if one fills a ball with inflammable air, much lighter than common air, the ball of itself will go up to an immense height of itself. This was the first publick experiment of it. at Paris. a Subscription was opened some time agone and filled at once for making a globe; it was of taffeta glued together with gum, and lined with parchment: filled with inflammable air: it was of a spherical form; and was 14 foot size in Diameter. it was placed in the Champ de Mars. at 5 o’clock great guns fired from the Ecole Militaire, were the signal given for its going, it rose at once, for some time perpendicular, and then slanted. the weather, was unluckily very Cloudy, so that in less than minutes it was out of sight: it went up very regularly and with a great swiftness. as soon as it was out of sight. More cannon were fired from the Ecole Militaire to announce it. this discovery is a very important one, and if it succeeds it may become very useful to mankind.”5

A Cincinnati connection

When I was reading Adams’ journal, an image came to mind of our annual Christmas visit to a historic restaurant in Lebanon, Ohio, called The Golden Lamb. I remembered seeing a room with his name on it, signifying that he had been a guest at the inn, so I decided to make a special trip there with my sister, Sarah, when she was in town recently.

The Golden Lamb

Twelve presidents have made a visit to The Golden Lamb, including John Quincy Adams, who came there to have his portrait pencil sketched. He also made a speech at the Cincinnati Observatory in an area that would be named after him in honor of his visit, Mount Adams.6

My sister and I enjoyed a delicious meal during our visit and proceeded to tour upstairs to find the room of John Quincy Adams. We weren’t able to locate it in the place where I remembered seeing his name.

We asked a couple staff members, who were immediately able to recall that due to guest complaints about the small size of the room, it had been combined with another that has the name of president Ulysses S. Grant.

We hope to share more adventures from The Golden Lamb at a future date. We look forward to our annual visits there, and it may be one reason we developed an interest in history from such a young age.

Conclusions

I enjoyed reading the observations of Adams in his youth during the Revolutionary Era. What I find interesting about all of these accounts so far is that for different reasons none of them expressed strong feelings of passion about the notion of American independence as you might expect in reading accounts of Americans during the Revolutionary Era.

Though each of them in hindsight played a role in the trajectory of the Revolution, their accounts demonstrate that in their perception they were simply doing everyday things that mattered to them with the events of the Revolution going on in the background. To me, it speaks of history as a collage of individuals with stories who collectively contribute to the outcome of an era, at times unbeknownst to them.

In Pt. 4 of The American Revolution from different perspectives, we will share some photos from a Cincinnati cemetery with graves dated from the Revolutionary Era.

://www.primarysourcecoop.org/publications/jqa/document/jqadiaries-v01-1779-11-p000--entry1?doci=undefined

https://www.primarysourcecoop.org/publications/jqa/document/jqadiaries-v08-1783-08-p001--entry5?navmode=chronological

https://www.primarysourcecoop.org/publications/jqa/document/jqadiaries-v08-1783-08-p001--entry6?doci=undefined

https://www.primarysourcecoop.org/publications/jqa/document/jqadiaries-v07-1783-09-p019--entry2?navmode=chronological

https://www.primarysourcecoop.org/publications/jqa/document/jqadiaries-v08-1783-08-p001--entry14?navmode=chronological

https://www.goldenlamb.com/news/the-golden-lamb-presidents-of-our-past/