Margaret Hill Morris writes to amuse her sister

The American Revolution from different perspectives Pt. 1

When one thinks of the Fourth of July, a number of images come to mind: fireworks, grill outs, summer, family get-togethers, and perhaps the image of the American Founding Fathers. This month I would like to share with you stories of the American Revolution, considered to span the years 1765 to 1783.1 These stories come from a few different vantage points that I believe give the reader a feel for the many facets of life in that era that impacted the population and how the population in turn impacted the era.

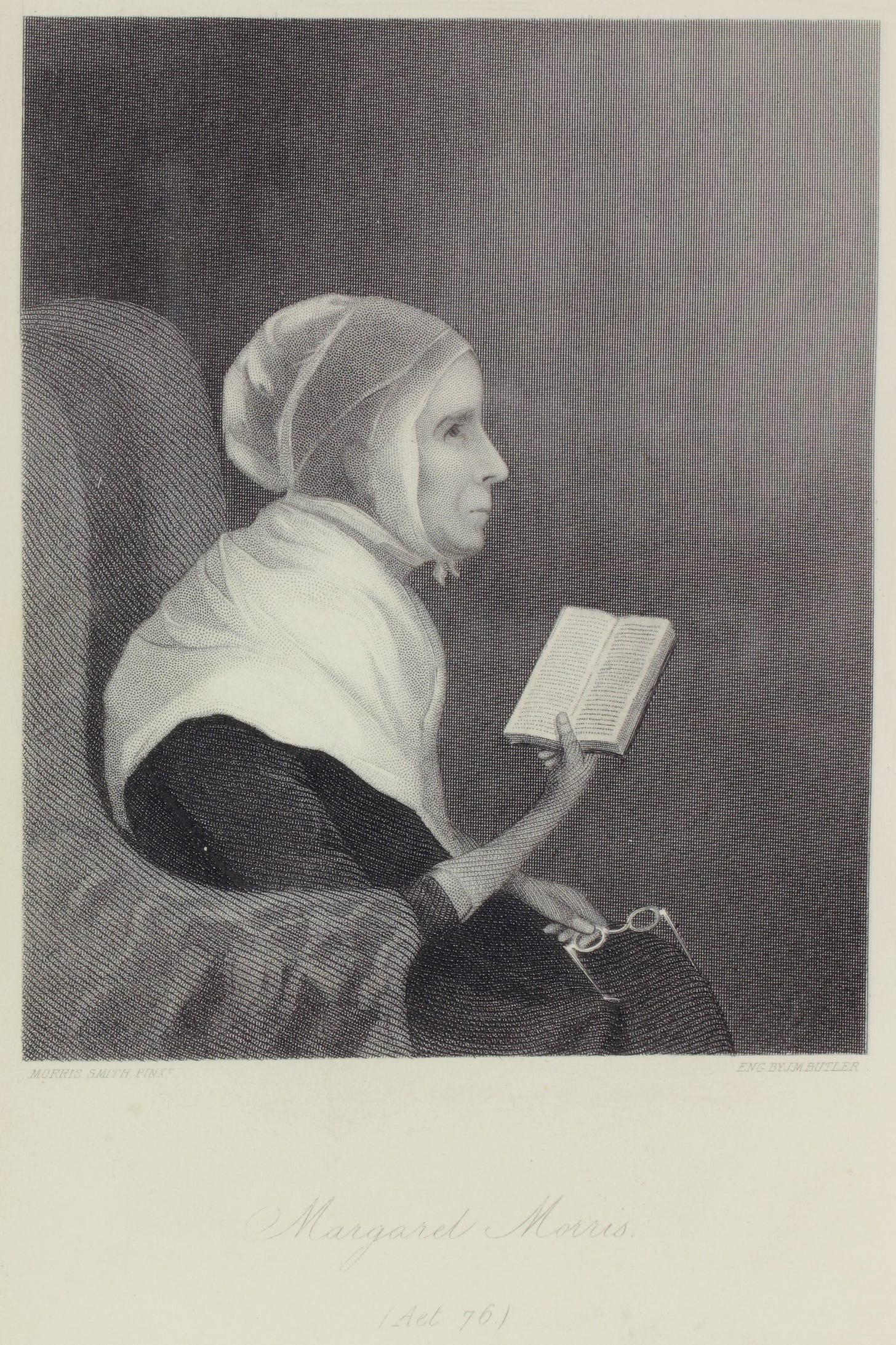

Perhaps the general public might not ponder the lore of the American Revolution over the Fourth of July. In the introduction to the journal of Margaret Hill Morris, her grandson who published her writing in 1836 states that, “though it may interest the antiquarian and historian of a future day, it is not designed for the public.” Owning the title of “an antiquarian of a future day,” I will share excerpts of Private Journal Kept During a Portion of the Revolutionary War for the Amusement of a Sister by Margaret Hill Morris in the hope that others may also enjoy the stories.2

Margaret Hill Morris, born in 1737, was the eighth child of Dr. Richard Hill and Deborah Moore of South River, near Annapolis, Maryland. Her parents moved in 1739 to Funchal, the Island of Madeira, Portugal, due to her father being in debt. Margaret was left in the hands of her sister, Hannah Hill Moore. Margaret ended up marrying William Morris, Jr., who came from a prominent Quaker family. Her husband died at the young age of thirty-one in 1766, and as a widow with four children, Margaret opted to move to Burlington, New Jersey, near her sister Sarah Hill Dillwyn, purchasing a house that had formerly belonged to the governor of New Jersey, William Franklin.3

During the Revolutionary War, Margaret kept a journal of her experiences, apparently for the amusement of her sister, Milcah Martha Moore, who was also a writer. In the journal she shares her experiences and thoughts over the course of the war.

The War Begins

When Margaret heard the news that “the English were coming,” she was visiting a friend in Haddonfield, New Jersey, and had heard reports that the English fleets were coming by river. She was told that people were going to flee to the countryside and burn the towns, including the town where she lived. This made her distressed to the point of sickness and faintness as she was concerned for the safety of her sister and brother-in-law, who were there. She longed for the comfort of her deceased husband in this frightening time, but ultimately reminded herself that she needed to trust in the will of God. She was relieved to find that when she arrived in her town, her family was okay and nothing had been burnt down.

Tory Hunting

Over the next few days Margaret related mostly peaceful negotiations between the Hessians (German troops hired by England) and the townspeople. Eventually, there was a reported ruckus of what Margaret calls “Tory hunting,” organized searches for Tories, or the colonists who remained loyal to the British Crown. When the Tory hunters arrived she was able to aid one who had taken refuge in her house to escape unnoticed.

Due to the Quaker belief in pacifism, neither Margaret nor her family believed in the concept of war and throughout her writings, she did not express support for the cause of the Revolution. In fact, she often communicated frustration with the conflict. In one entry in her journal, she describes her forgiveness toward a man killed in battle who had previously threatened to kill her son. The threat happened in response to her son using his spyglass to watch the war ships arrive. She wrote, “what sad havoc will this dreadful war make in our land!”

A Not So Jolly Christmas

In one grievance that Margaret shared, she referred to the reason the Hessians had not been able to win a battle that she says occurred on the early morning of December 25th but likely took place on the morning of December 26th.4

“It seems that the heavy loss to the regulars, was owing to the prevailing custom of the Hessians, of getting drunk on the eve of that great day which brought peace on earth, and good will to men.”

This event, which is known as the Battle of Trenton and is remembered for Washington’s daring crossing of the icy Delaware River, greatly troubled Margaret.

Itch Fever

Margaret was eventually asked to provide to the ailments of the injured soldiers as she had experience in providing medications to the poor. Initially she was a bit afraid that it was a ruse to pillage her home, but she agreed to do this. She ended up servicing individuals on both sides of the war. She said that several soldiers came down with illness. Margaret began to refer to this ailment as “itch fever,” which in modern terms is known as yellow fever. Margaret is believed to have provided care to over thirty individuals with yellow fever.5

At one point, she lamented that George Washington would not agree to a general’s request to a three days arms cessation so that the wounded could be tended to and the dead buried. She stated, “what a woeful tendency war has to harden the human heart against the feelings of humanity. Well may it be called a horrid art-thus to change the nature of men! I thought that even barbarous nations had a sort of religious regard for their dead.”

A Visit Home

A Rebel quarter-master, who Margaret had provided care to, offered to take her to visit her family in Philadelphia. Margaret, overjoyed, chose to make the journey in the midst of war along with a friend. The trip was nerve racking, but they were able to make it there and back home safely. When she arrived back to Burlington, she was encouraged by her friends to never again make such a perilous journey. Margaret answered, “our late expedition, far from being a discouragement, was like a whet to a hungry man, which gave him a better appetite for his dinner.” By the way, whet is a word defined by the Oxford Languages dictionary as, “a thing that stimulates appetite or desire.” It is also a word approved in the Scrabble dictionary, so be sure to add that to your collection.

Conclusion

Margaret Hill Morris’s journal gives a tiny glimpse into life during the Revolutionary era. Her story speaks of hoping for the best in times of turmoil. And if things get troublesome remember: there is always the option of writing a journal to amuse your sister!

In Pt. 2 of The American Revolution from different perspectives, I will share a story of the American Revolution from the viewpoint of a Black soldier in the Continental Army.

Morris, Margaret Hill, Private Journal Kept During a Portion of the Revolutionary War for the Amusement of a Sister. Privately Printed. 1836.

“Margaret Hill Morris”. Wikipedia. May 4, 2024.

Trenton. American Battlefield Trust.

Bulletin of Friends’ Historical Society of Philadelphia, May, 1919, “The Revolutionary Journal of Margaret Morris, N.J., December 6, 1776 to June 11, 1778,” Friends Historical Association, Philadelphia.

This was fun to write. I enjoyed her bit of ornery thoughts, it made me laugh a little.