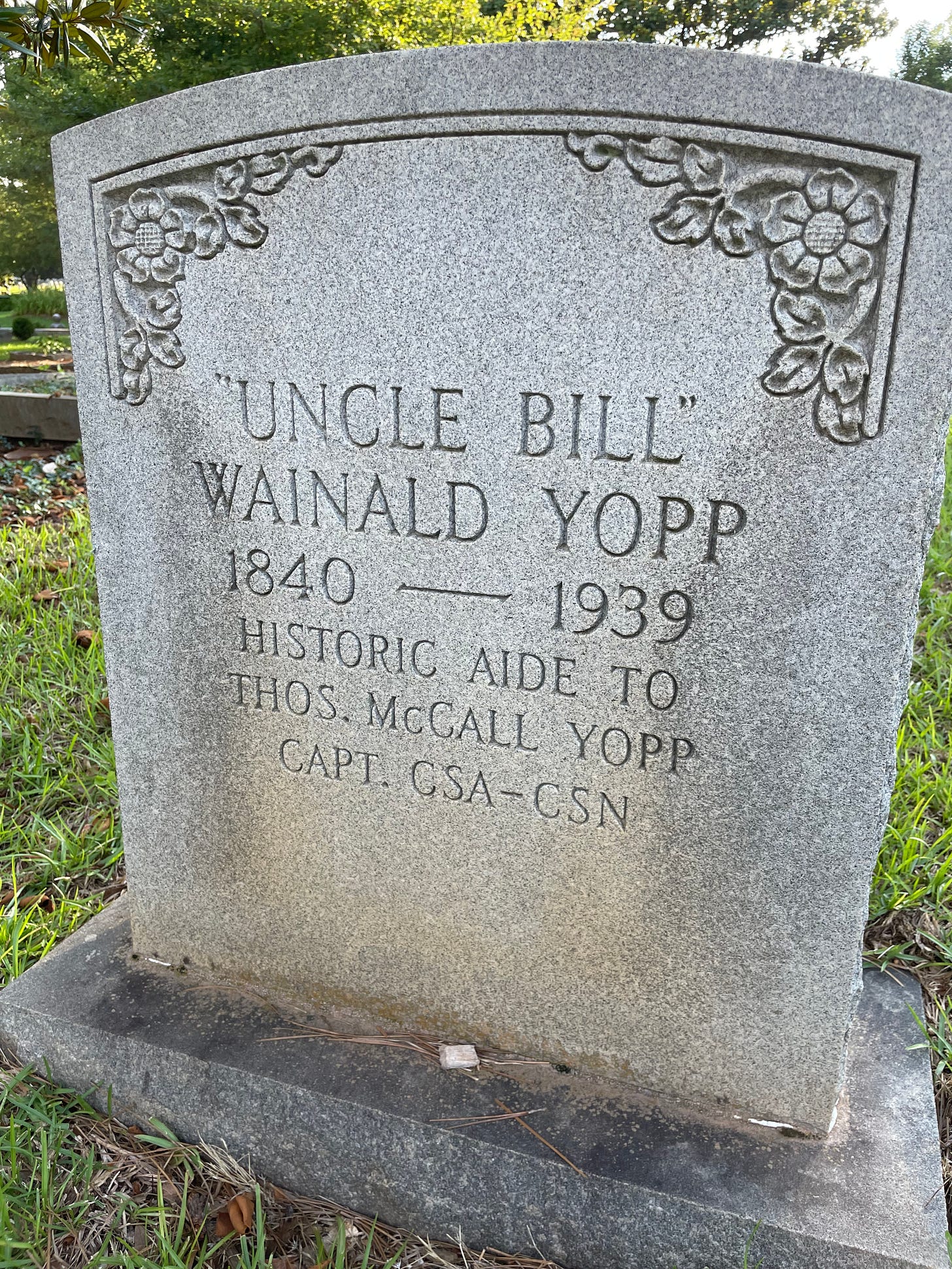

Today, I want to share the story of Bill Yopp, a man whose marker I ran across in the Historic African American section of Atlanta’s Oakland Cemetery a few years ago, and whose life story shares similarities to another cemetery resident, William Finch, who is the impetus for this series.

Here is the dilemma I face in trying to share Bill Yopp’s story. Much has been written about him, especially in Atlanta newspapers, between 1917 and his death in 1936, but the information shared about him is at times contradictory and the narratives seem designed to support the “loyal slave” myth that is a key ingredient in Lost Cause ideology (as discussed in last week’s post).

More recently, Yopp’s role in the Civil War has been misrepresented as that of a Black Confederate soldier, which is used as evidence for Black support of the Confederate cause and obscures the fact that he went to war to serve his enslaver (see Kevin Levin’s book Searching for Black Confederates: The Civil War’s Most Persistent Myth and check out his Substack, Civil War Memory).

As a history enthusiast rather than a historian, I feel like I’m wading into waters that are difficult to tread, and these waters are also hot, contentious, like thermal springs with a sign warning would be swimmers of danger.

I know I’m entering at my own risk, and here’s what I’m afraid of: (1) if I relay Yopp’s story as it has been told in the past, I risk reproducing a Lost Cause narrative that has been used as a way to discount slavery’s central role in the Civil War; (2) if I present his actions as a response to the constraints of the time and try to reframe them as an act of resistance to slavery, a storyline more palatable in our modern era, I risk taking agency from Bill Yopp; and (3) why am I, a 21st century white woman with no connection to Bill Yopp other than spotting his grave and then bingeing stories about him on newspapers.com, trying to tell his story anyway?

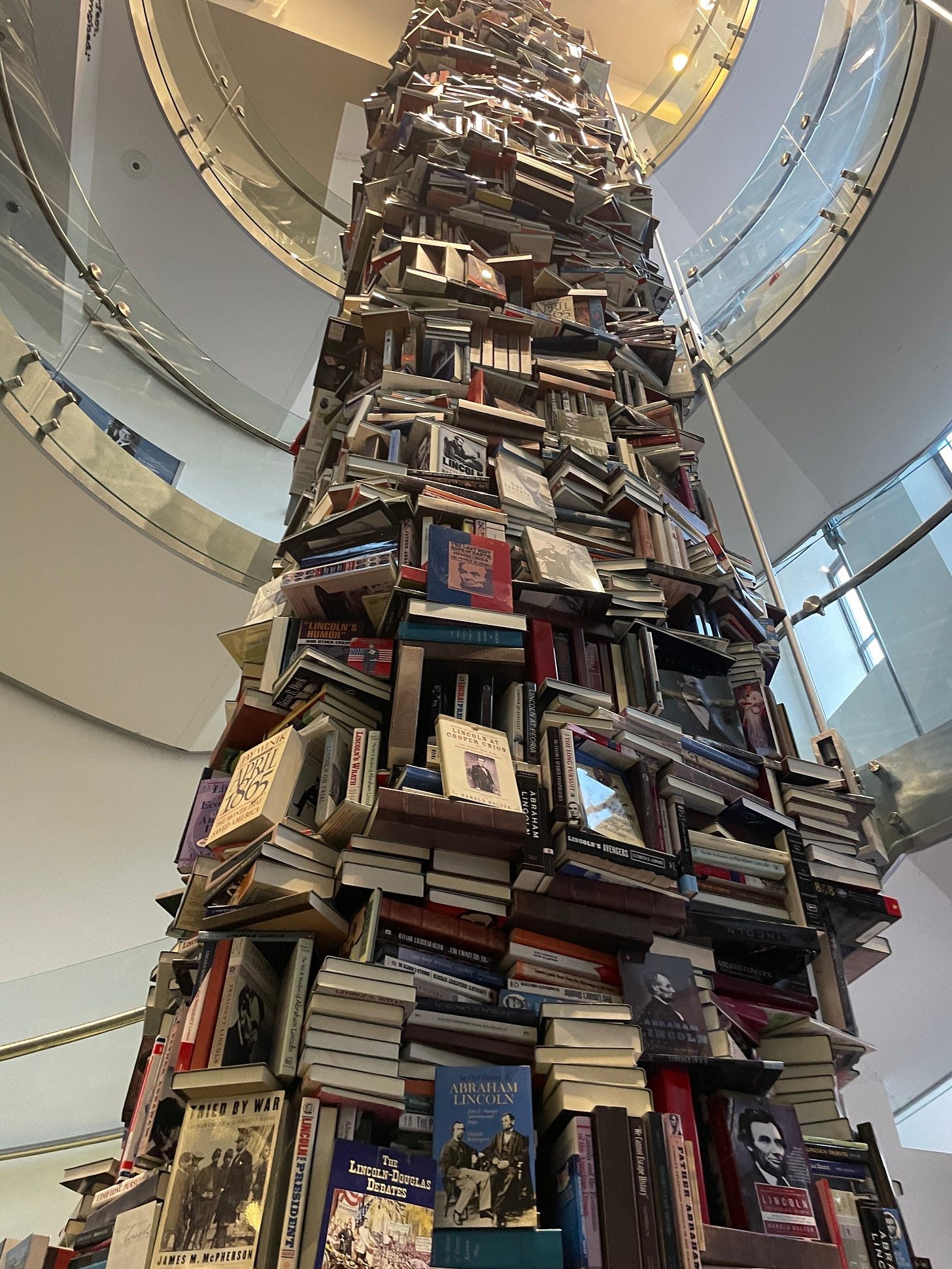

I’ll address my last fear first, and say that one realization I’ve been coming to recently about the interplay between memorialization and historical knowledge is that memorialization, by venerating only a few or a select group, can obscure the larger historical picture. Everyone alive in the North and the South at the time of the Civil War, including Bill Yopp, had an experience of the conflict, not just the politicians who made decisions and the generals who rode horses. Instead of focusing all our attention on the actions of men at the top (sorry, patriarchy), we can learn more by examining a multitude of stories. How many books about Lincoln do we really need?

Bill Yopp

With all the caveats from above and another that this information is difficult to fact check, here is the gist of Bill Yopp’s story as I’ve gathered from what I’ve read.

Yopp was born into slavery and worked on the Yopp plantation in Laurens County. As a young boy, he was assigned as a servant to Thomas, his enslaver’s son, and when Thomas joined the Confederate army, Yopp accompanied him to the war. One way Yopp was said to have acquired the nickname “Ten-Cents Bill” was that he would charge ten cents for any job that the soldiers in camp wanted done.

Thomas was injured during the war, and Yopp helped to nurse him back to health. After the war, Yopp eventually left Georgia and traveled around the country (possibly the world). He’s said to have served US presidents. Eventually, he came back to Georgia and worked as a porter at the Georgia capitol building.

As a poor elderly man, Thomas lived at the Confederate Soldiers’ Home in Atlanta. Yopp is said to have visited him there regularly and offered Thomas financial assistance.

In the late 19-teens, Yopp campaigned at the statehouse for more monetary support to be given to the Confederate veterans who lived in the home. He also collected money during the holidays for the residents of the home and raised money for them by selling a pamphlet that told his life story (which I should have access to soon). His penchant for collecting ten cent donations is also cited as a way he earned the nickname “Ten-Cents Bill.”

It is reported that Yopp was at Thomas’s beside when the latter died, and Yopp spoke at the funeral. Around this same time, Yopp was awarded a gold medal and he was given a place to live in the Confederate Soldiers’ Home in recognition of his efforts to raise money for the veterans.

Yopp was still living in the home at the time of his death in 1936, and he was buried in the Marietta Confederate Cemetery. The marker in Oakland Cemetery is a cenotaph.

I don’t want to speculate too much on why Bill Yopp did what he did for Confederate veterans, but I do want to share a quote that seems to hint at his motivation. In an October 21, 1934 interview in The Atlanta Journal with Jennie Sue Daughtry, Yopp is quoted as saying this:

All my life I have tried to do for others. And now I know that good deeds are not buried. They live.

I’ve been listening to a series of lectures by Ari Shapiro on The Power of Storytelling, and I learned today that a good way to change course when an interview subject is uncomfortable or when a conversation becomes too intense is to use the phrase, “let’s talk about something less serious.”

So, let’s talk about something less serious…

Daffodils

I visited the Spring Bulb Show at the Lyman Conservatory on the Smith College campus last week and saw some incredibly beautiful daffodil varieties.

I like the open-endedness of this.