The self-sacrificing devotion of women

How memorialization has reinforced patriarchy and disrupting the cycle

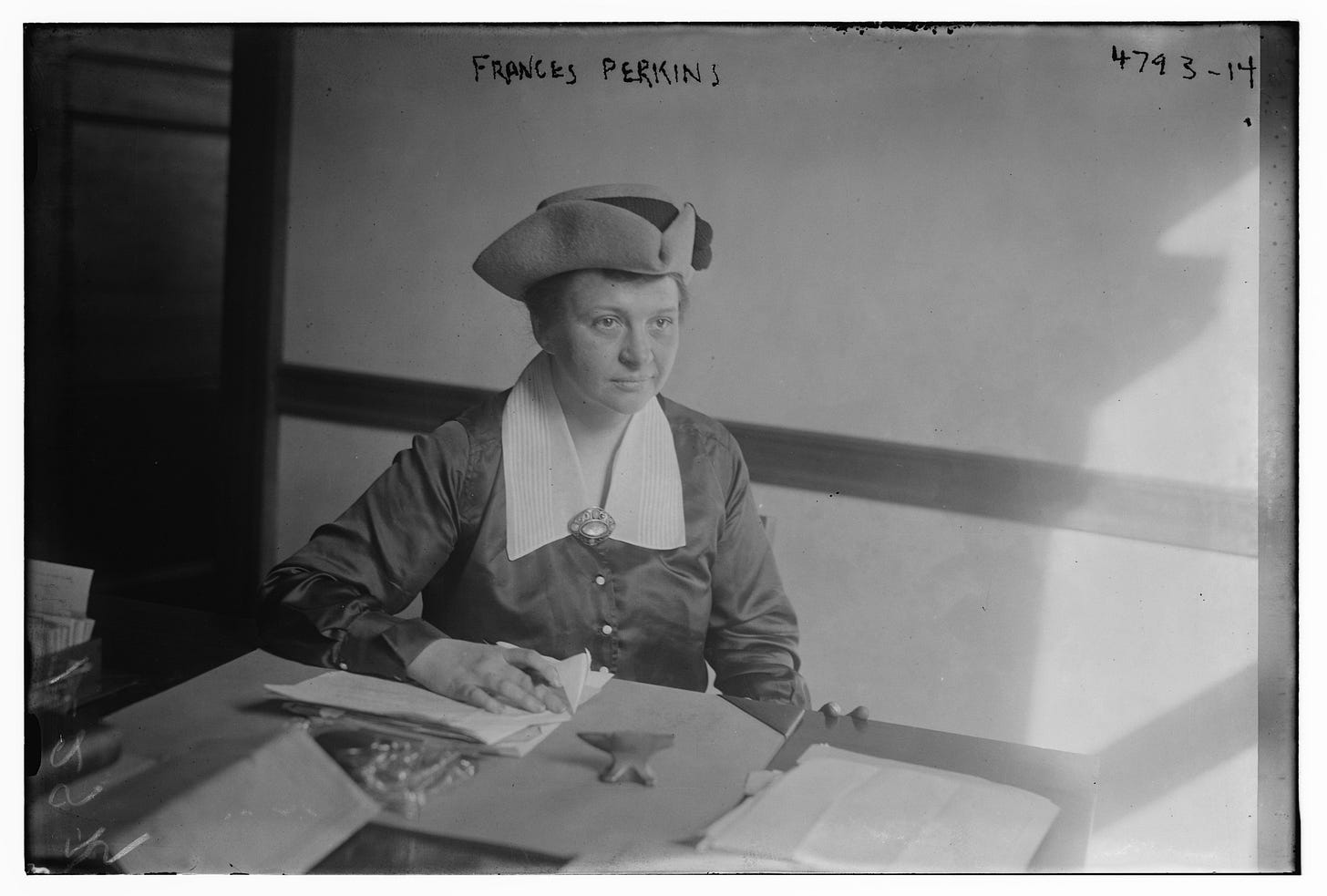

This week I saw a news headline about a campaign to designate the Maine childhood home of Frances Perkins a national monument. Perkins was the first woman to serve in the cabinet of a US President. In her role as Secretary of Labor under Franklin D. Roosevelt, she was a driving force behind the New Deal.

According to the biography available from the Frances Perkins Center, her acceptance of the position was conditional on FDR allowing her to focus on these priorities: “a 40-hour work week; a minimum wage; unemployment compensation; worker’s compensation; abolition of child labor; direct federal aid to the states for unemployment relief; Social Security; a revitalized federal employment service; and universal health insurance.”1 The only priority she failed to achieve while in office was universal health insurance.

In March of this year (2024), President Biden issued an executive order calling for better representation of women’s history in the National Park System. Around the time the order was issued, only 76 national parks, historic sites, and monuments were named after women or focused on women’s history out of a total of 476.2

Hopefully, Frances Perkins’s Maine home will be added to this list soon.

The woman behind the Brooklyn Bridge

Frances Perkins’s story reminded me of another woman, Emily Warren Roebling, whose memorials I ran across on a recent visit to the Brooklyn Bridge in New York City.

The Brooklyn Bridge was planned by John Roebling, who was also behind Cincinnati’s Roebling Bridge that spans the Ohio River. The latter was the longest suspension bridge in the world when it opened in 1866, but it’s length would be surpassed by the Brooklyn Bridge in 1883, nearly two decades later.

While scouting the location for the Brooklyn Bridge in 1869, John Roebling’s foot was crushed by a ferry, and soon afterward, he died from tetanus. His son, Washington Roebling, took over the role of chief engineer.

As part of his work, Washington Roebling would go down into the depths of the East River in pressurized chambers called caissons. Not as much was known then about safely returning to the surface, and as a result, Washington Roebling suffered from what is known as decompression sickness or “the bends.” He became bedridden with the illness and was no longer able to monitor the day to day operations of the bridge construction in person. Emily Warren Roebling, his wife, took over his public facing duties and helmed the project for over a decade.

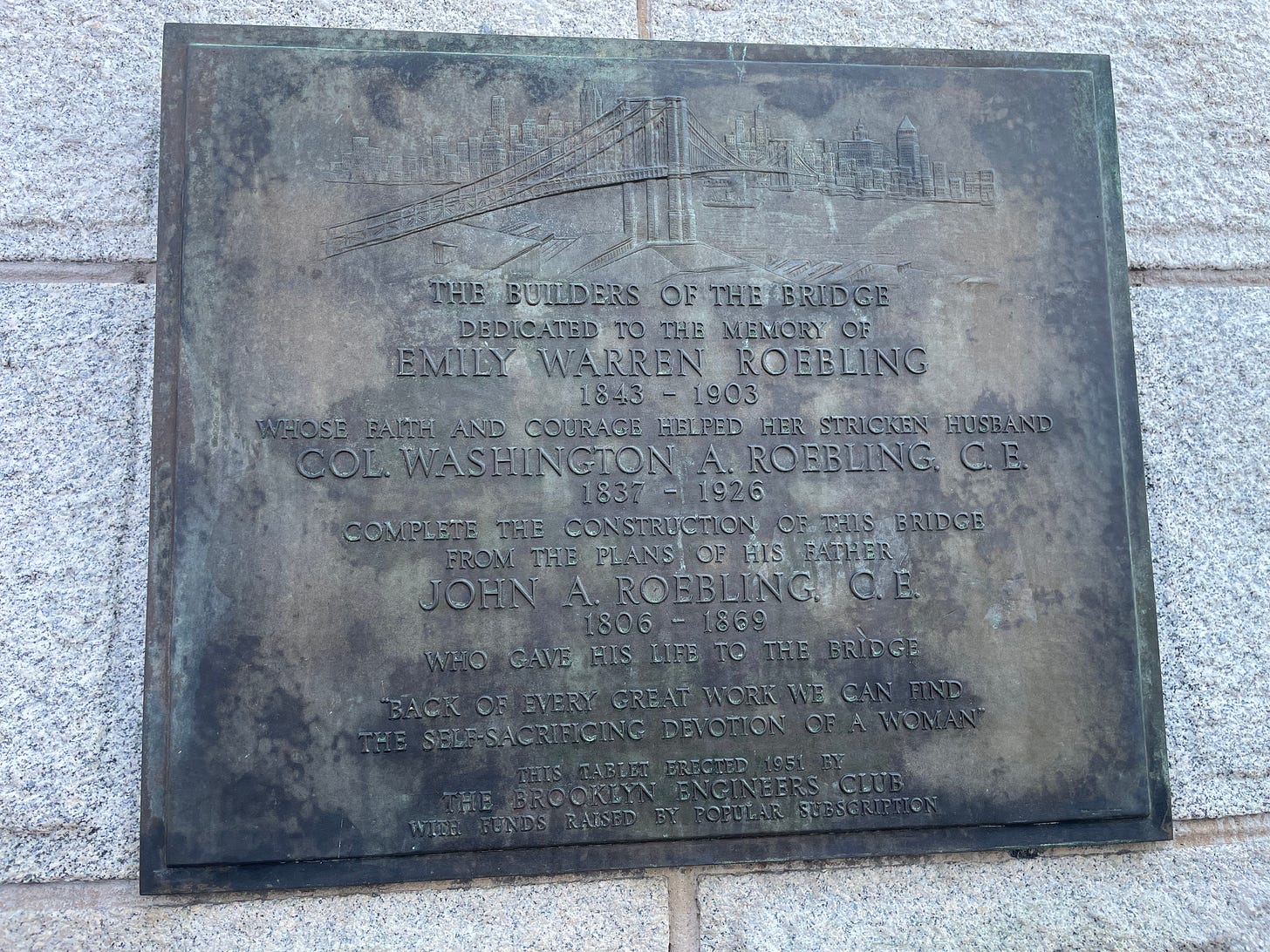

A plaque acknowledging her role as a builder of the bridge was mounted in 1951:

She is the first person listed, but her efforts are described like this: “whose faith and courage helped her stricken husband…complete the construction of this bridge from the plans of his father…who gave his life to the bridge.”

Then, there’s a quote: “back of every great work we can find the self-sacrificing devotion of a woman”

More recently, in 2021, the Emily Warren Roebling Plaza opened beneath the Brooklyn Bridge. I didn’t capture a photo of the interpretive panel there outlining her contributions, but an internet search suggests the text is similar to what can be found under the Emily Warren Roebling section of this page about Brooklyn Bridge Park.

Bringing women to the forefront of history

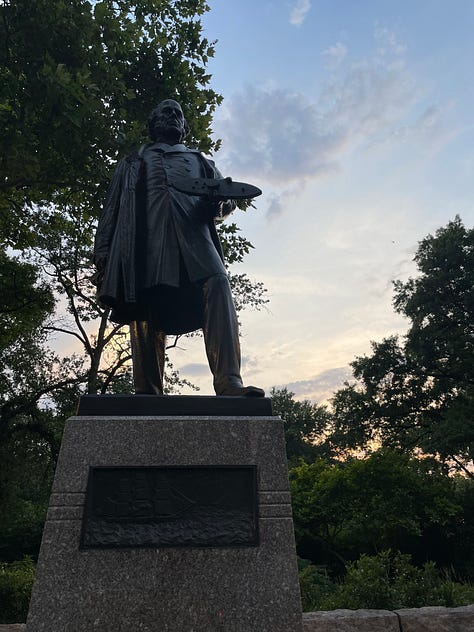

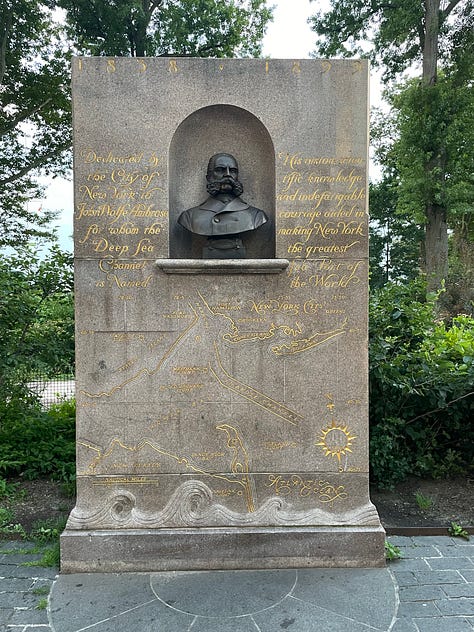

One thing that struck me on my recent trip to New York City and Boston was how many memorial statues of men I passed on the street.

This ubiquity of these statues is a testament to men’s greater access to positions of power in the past. During these times, women were more likely to be celebrated for their contributions behind the scenes (as the quote from the 1951 plaque honoring Emily Warren Roebling suggests).

Biden’s recent executive order aims to redress the imbalance and celebrate women as major players in history; however, the existing memorial landscape is so heavily male skewed that it’s hard to envision exactly how women could catch up.

Should only women be honored for the foreseeable future? Should memorials to men be taken down? Should the whole practice of memorialization be rethought given that in the past it has mainly served to highlight the accomplishments of white men?

If the answers to these questions were easy, I wouldn’t be writing The Silent Sod.

The future is female

This past Spring, Emily Warren Roebling, who died in 1903, received an honorary degree from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute where her husband and son earned their degrees in engineering. At the commencement ceremony, Roebling, as portrayed by actor Liz Wisan, delivered an address that was developed by generative AI trained on her texts with some human editing. You can watch those remarks here:

https://francesperkinscenter.org/learn/her-life/

https://www.outsideonline.com/outdoor-adventure/hiking-and-backpacking/national-park-service-increase-recognition-women/