Where were Black Atlantans during the Confederate Memorial Day parade in 1874?

William Finch & Daffodils Pt. 6

There’s an improv troupe currently taking the stage at Dad’s Garage in Atlanta called Blackground. The premise of their format is taking a classic movie that has a majority white cast (e.g., Star Wars or Indiana Jones) and showing what Black people were doing during the film. I didn’t have the chance to catch Blackground while I was visiting Atlanta this past weekend, but years ago, I saw an earlier iteration of this show and was a big fan.

I spent the majority of my time in Atlanta hanging out at Oakland Cemetery attending Illumine, a special after dark arts event, and giving tours. I realized after I’d booked my travel dates that I would likely also be there on the 150th anniversary of the dedication of the Confederate Obelisk, a Confederate memorial at the cemetery. The dedication happened in 1874, nine years after the war ended, on what was known then and is still recognized in some Southern states as Confederate Memorial Day (no longer officially in Georgia).

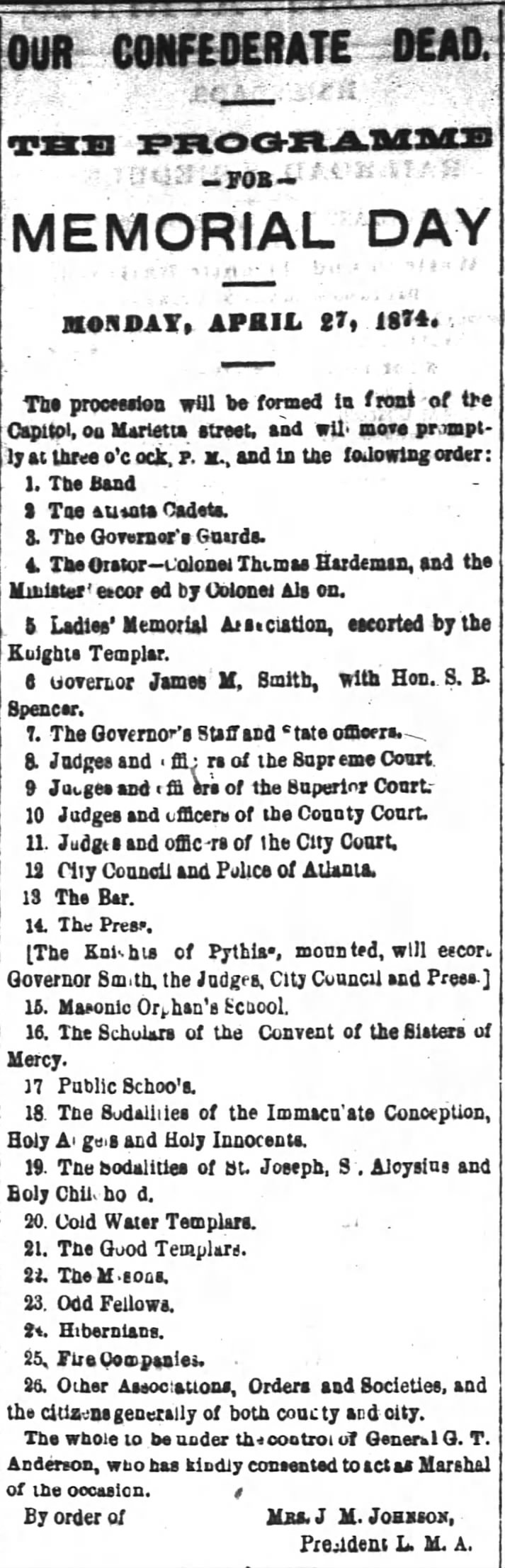

I was curious of the exact date of the dedication so I turned to my trusted source, newspapers.com, and found a couple of pieces confirming that it occurred on April 27, 1874. The first was an announcement listing the order for the parade connected to the dedication, which underscores how participants represented all levels and branches of government as well as many civic organizations of the period:

I also found a news report published after the dedication that indicated around 15,000 people attended the event and that the parade route was crowded “with a moving mass of humanity, of all ages, sexes, and sizes.”

The reporter’s use of the terms, age, sex, and size, made me wonder whether there was variation in another demographic variable: race. Were Black people in Atlanta, like William Finch who has been the focus of this series, in attendance at the Confederate Memorial Parade in 1874? If not, what else were they doing while this massive event was happening?

I would assume Black people weren’t there, but I’m aware of another Confederate themed parade, this one happened in 1886, that included Black school children. I first heard about this later parade in connection with Antoine Graves, who like William Finch rests in the Historic African American section at Oakland Cemetery.

In 1886, Graves was the principal of the Houston Street School, which served Black students. Children attending this school were asked to take part in a celebration welcoming Jefferson Davis, the former president of the Confederacy, when he came to Atlanta for the dedication of a statue of Benjamin Hill.

As a tour guide, what I’ve learned about Graves is that he passed along this invitation to the students and teachers at his school but said that he would not attend and pay tribute to Davis since the former Confederate president had fought to keep Black people enslaved and without education. Graves’s act of resistance, which I regard as similar to Finch’s presentation of the American flag to Union troops, is said to have resulted in him losing his job and potentially fleeing the state for a time.

Of course, already down the newspapers.com rabbit hole about the 1874 parade and dedication, I had to look up the 1886 event as well. I was able to confirm from this news article that students from three schools which served Black children (Summer Hill, Mitchell, and Houston) were included in Jefferson Davis’s welcome parade along with white schoolchildren. The children lined the streets between the railroad depot and Mrs. Hill’s house (Davis’s destination), and they were responsible for throwing flowers ahead of Davis’s carriage “at a distance sufficiently in advance not to startle the horses.”

One thing that interested me about the article outlining how the 1886 reception for Davis would proceed was that it specified that priority viewing spots would be given to “the children and young people who have grown up since the war.”

When I first moved to Atlanta in 2011, some of my friends from Berkeley asked me how I was going to handle living in a place with so many Confederate monuments. I said I didn’t think it would be a problem for me since I saw them as an expression of grief from people who had lost loved ones in the war. What I didn’t know then that I do now is that a lot of Confederate monuments were erected decades after the war. By paying tribute to Confederate leaders and ideals, these monuments reinforced white supremacy and Lost Cause ideology while ignoring the most significant outcome of the war: the emancipation of four million enslaved people.

The Confederate Obelisk is an earlier monument, dedicated nine years after the end of the war, and it is located in a cemetery where over 6,900 Confederate soldiers are buried. Some would argue that these facts exempt it from a list of problematic monuments, but others would say that any monument that pays tribute to an armed force that fought to preserve slavery is problematic.

As far as I could tell, there was no observation of the 150th anniversary of the dedication of the obelisk at Oakland Cemetery this past weekend. I spent some time reflecting on what a parade of 15,000 people would have looked like on the cemetery grounds and the logistical problems it would have presented. I thought about what the dedication had meant for the women from the Atlanta Ladies Memorial Association who were responsible for the erection of the monument and the burial of unknown soldiers in the cemetery. I thought about what the day would have meant for William Finch and other formerly enslaved Atlanta residents whose emancipation was secured by the Confederate loss. As I’ve argued in other posts in this series, I think our understanding of history grows richer when we consider a broad range of experiences rather than just focusing on one group or the leaders of the time.

The Daffodils

As always, these posts come with a side of daffodils. I unfortunately missed daffodil season in Atlanta entirely, but the ones in Amherst are still going strong. I was especially impressed with this bounteous display I found recently in a shopping plaza.

That story is interesting that he lost his job over not going to this parade. Stories of resistance, it took courage!