In February, I visited Arlington House, which is also known as The Robert E. Lee Memorial, inside Arlington National Cemetery. Robert E. Lee was a general for the Confederate army during the Civil War, and early in the conflict, his house in Virginia was seized by Union forces because of its strategic location relative to Washington DC. Near the end of the war, Union soldiers were buried on the property because other nearby cemeteries were full, and these burials represent the beginning of Arlington National Cemetery, which today operates as a US military cemetery with over 400,000 burials.

Given the controversy surrounding Confederate monuments in recent years and government legislation that has required renaming US military installations honoring Confederate soldiers, I was interested to see what sort of information was being shared at Arlington House, which is run by the National Park Service.

I spent about three hours at Arlington House (at the expense of seeing pretty much anything else in the cemetery). There’s a ton from my visit that I hope to share here eventually.

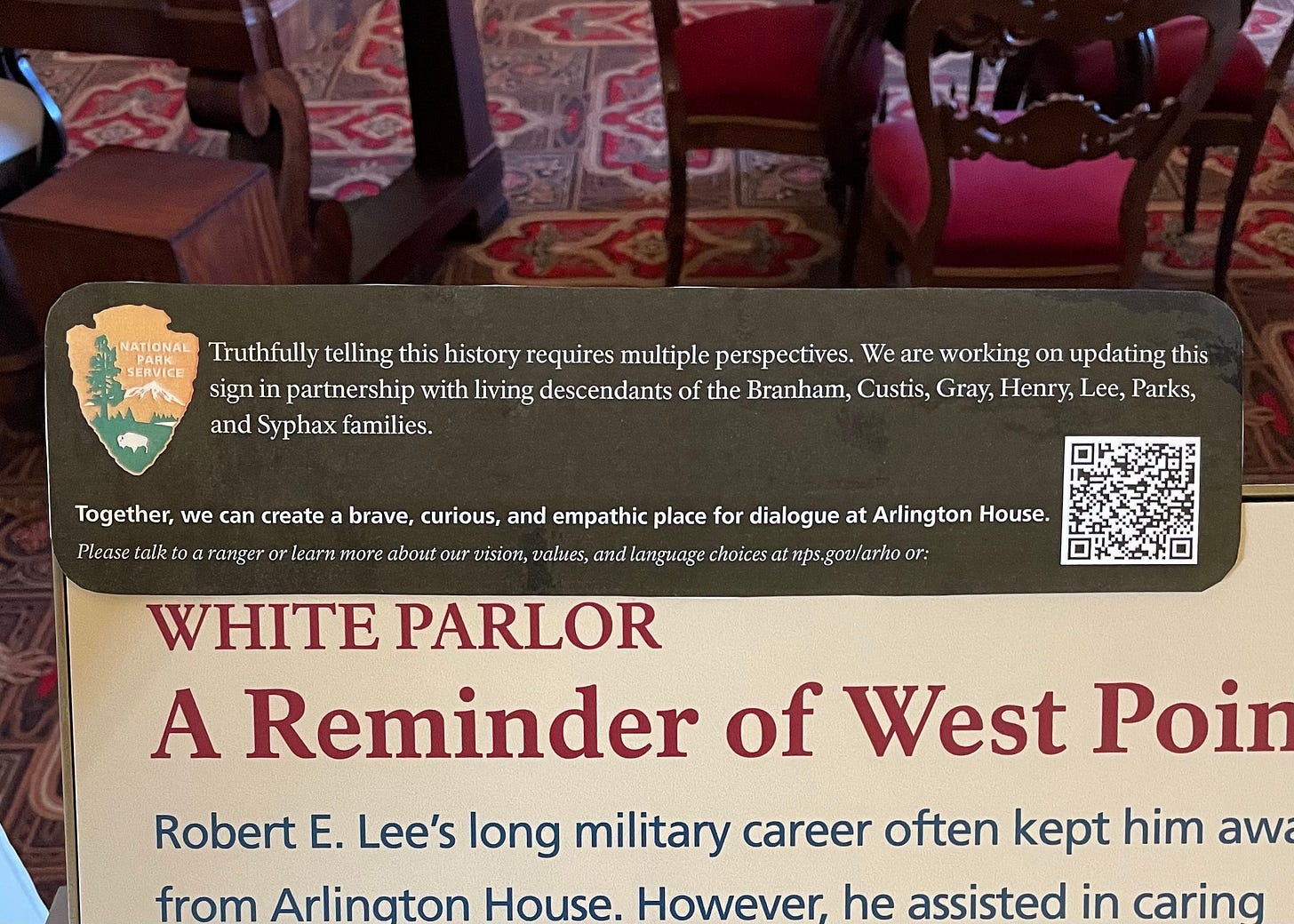

What I’d like to focus on today, though, is the disclaimer that I found on many of the informational placards. (Note: the QR code leads to a Visitor Expectations and Language Resource page on the NPS website, which I encourage you to check out.)

A little bit of background on Arlington House to help decode this message. George Washington Parke Custis inherited the land the house was established on from his grandmother, Martha Custis Washington. He also inherited the people she enslaved, and these enslaved laborers built the house.

G.W.P. Custis planned for Arlington House to serve as a tribute to his step-grandfather, America’s first president, George Washington, whose household G.W.P. Custis had lived in as a child. After G.W.P. Custis’s death, his daughter, Mary Custis Lee, the wife of Robert E. Lee inherited the house and that’s how the Confederate general came to live there. So, what’s known today as the Robert E. Lee Memorial was actually built to be a memorial for George Washington.

During their time at Arlington House, both the Custis and Lee families relied on enslaved labor. The families living there included the Syphax, Burke, Parks, and Gray families. In recent years, the National Park Service has added an exhibit in the former slave quarters to share their stories. Touring this space and learning about the wider world of Arlington House hit home for me how much we miss out on in history by only focusing on men at the top like Washington and Lee.

I found this video featuring the descendants of enslaved persons who lived at Arlington especially illuminating.

To sum up what I perceive to be the changes taking place in the messaging at Arlington House:

The National Park Service is looking to tell a much broader story that includes all past residents regardless of their status as enslaved or free. They are pushing back on narratives that reinforce Lost Cause myths (e.g., slaveholders G.W.P. Custis and Robert E. Lee were “good masters”, the people they held in bondage were “loyal slaves”). In order to tell a fuller story, NPS is working with the living descendants of all of the residents of Arlington House, and they consider this approach a good model for how we as a country can examine the thornier parts of our history.

William Finch’s Descendants

For the past several weeks, I have been highlighting the stories of William Finch, Bill Yopp, and other men buried in the Historic African American section of Atlanta’s Oakland Cemetery and examining my role in sharing these stories as a white writer/tour guide.

The other day while I was browsing videos on Oakland Cemetery’s YouTube page, I came across a couple of videos that feature Kamaria Finch, a descendent of William Finch. Before I go any further in my series, I wanted to be sure to highlight these.

In the videos, Kamaria Finch discusses her great-great grandfather’s achievements and the impact he had on the Finch family and the greater Atlanta community, especially with regards to promoting public education.

This first video primarily focuses on William Finch’s role in education:

This second one is longer and examines other aspects of Finch’s life and legacy, including how his political involvement put him and his family at risk.

This week’s daffodils

Daffodils are finally in bloom in Amherst just in time for what was hopefully the last snow of season. I love how this daffodil looks like a bird taking flight. Reminds me of freedom and how important that right is.

This was a great read I really liked the videos that were included as well!